Adventures in Listening, August 25, 2023: Boom or Bust

Rhiannon Giddens highlights her original songwriting, while bluegrass virtuoso Molly Tuttle draws inspiration from the American West. Plus: Taylor Swift's songs of experience.

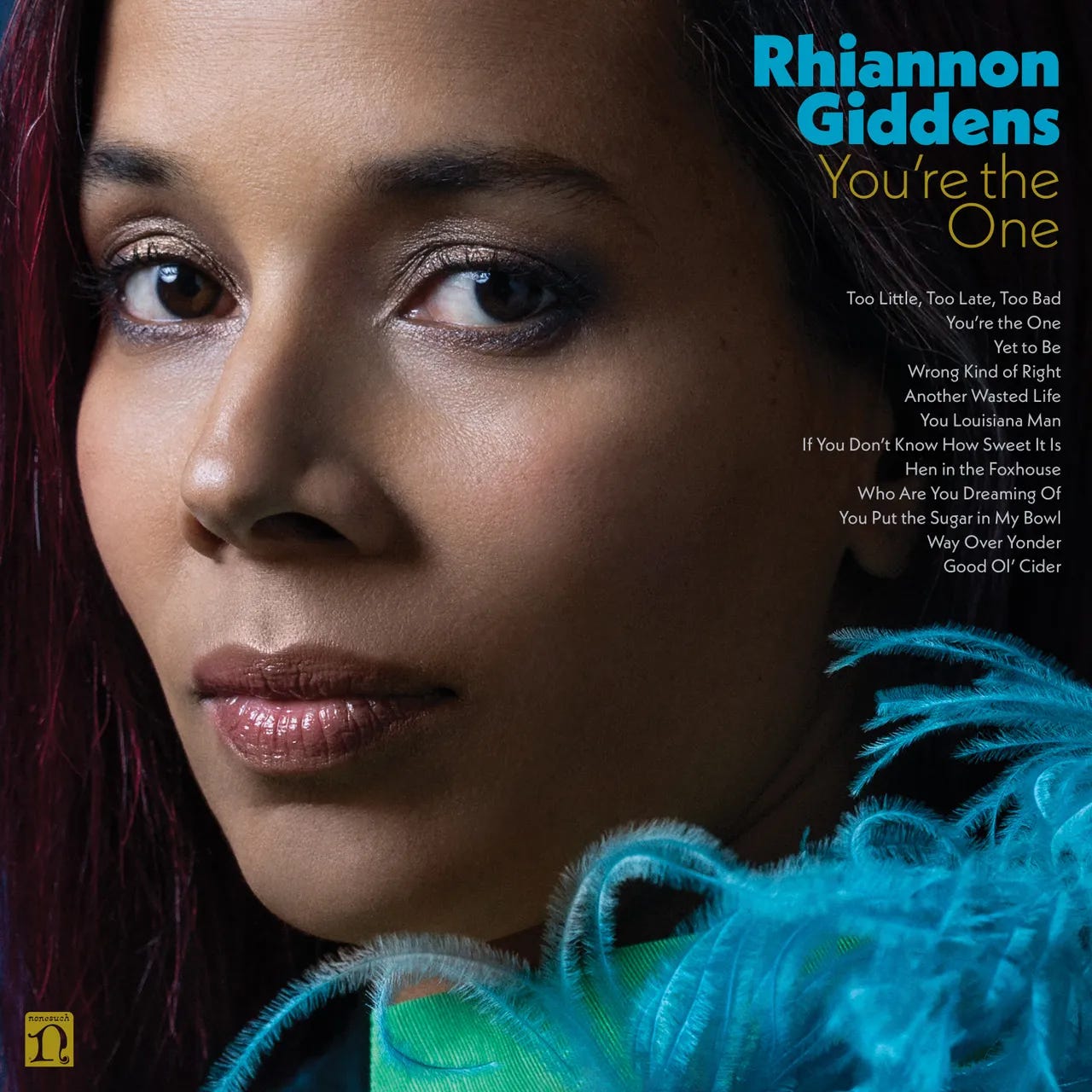

Rhiannon Giddens - You’re the One

Earlier this summer, I had the pleasure of seeing Rhiannon Giddens play a show in my hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee, jamming with Chris Thile and Yo-Yo Ma beneath the golden glow of the Sunsphere. Early in the performance, Giddens introduced one of her songs by explaining that it was a condensed summary of the American slave trade, and the ongoing legacy of violence against Black bodies. Then she offered a little quip to alleviate the tension: “Yeah, I’m a lot of fun at parties.”

Much of Giddens’ career has been spent as a folklorist, reviving and relitigating ancient traditions in order to recenter the contributions of Black musicians to American folk music (see the Carolina Chocolate Drops), to dignify the lives and stories of African slaves and their descendants (see Our Native Daughters), and to highlight the porous, interconnected nature of global forms and idioms (as on her beautiful albums with Francesco Turrisi). This is good and important work, and it’s made her one of the most singular and serious figures in music today— but on You’re the One, her first album of all-original material, she’s finally taking a bit of a vacation, deliberately stepping away from some of the heavier sociopolitical implications of her usual projects.

She goes as far as to recruit producer Jack Splash— he’s collaborated with everyone from Kendrick Lamar to Alicia Keys, and he made an especially great record with Valerie June a few years back— and to flesh out her oft spartan songwriting with propulsive tempos and lively production flourishes. To call this a contemporary pop album wouldn’t be right at all— structurally, Giddens is still interested in folk forms, from percolating Zydeco tunes to big band torch songs— but it certainly boasts a level of polish that none of her albums can claim.

And yet, despite a notable aesthetic shift, I feel like Giddens isn’t someone who vacations well; even embarking on a busman’s holiday, she can’t quite take her mind off her day job. Amidst gestures toward a carefree joi de vivre, she can’t help throw in a scabrous five-minute meditation on the failures of our criminal justice system (“Another Wasted Life,” a great addition to her party repertoire). And it’s hard for me to imagine a classically-trained singer like Giddens ever sounding like she’s ceded control or given way to a moment of abandon. Her precision can be a feature— check her commanding sense of melodrama on “You Put the Sugar in My Bowl,” a bawdy blues that tips its hat toward vaudeville— but just as often it’s a bug. “Too Little, Too Late, Too Bad” feels so buttoned-down that its romantic desperation never quite hits; Giddens is sending a wayward lover packing, but the formality of her delivery softens the blow and dampens what should be a palpable sense of glee.

And this is really what keeps the entire album from succeeding on its own terms: Giddens runs through song after song inspired by American folk traditions, from country to R&B, but they’re all expressed through boilerplate sentiments that favor formalism over emotional impact. When she dresses down her partner on “Too Little, Too Late, Too Bad,” there’s no bite to it: “I’m getting mighty tired of your little infatuations/ So now I’m gonna change my situation.” “If You Don’t Know How Sweet It Is” treads similar territory, and feels similarly limp and fussy: “I treated you like a King, maybe that’s the reason/ Soon enough you grew to think that Christmas was all-season.” The song’s righteous anger is undercut by its own decorum, only escaping its good manners with a well-placed “get the hell on out” at the very end. “You Put the Sugar in My Bowl” is difficult to resist, but even it channels its lust through old-timey vernacular ("you put… the pep in my step,” “you got me beggin’, papa, please”).

Her writing is so deliberately old-fashioned, and her delivery so careful and immaculate, that You’re the One winds up feeling like another example of Giddens doing her usual thing— only without the benefit of words and melodies that have stood the test of time. Only on the title song, a nakedly earnest expression of maternal wonder, does it feel like we’re hearing from a different Rhiannon Giddens, not the acclaimed folklorist we’ve come to revere. By and large, the album sounds like the artist is hiding behind folk forms, so consumed with wrapping up her homework that she forgot to plan the big party. And in that sense, it doesn’t tell us anything about Giddens that There is No Other or Tomorrow is My Turn didn’t already demonstrate more ably.

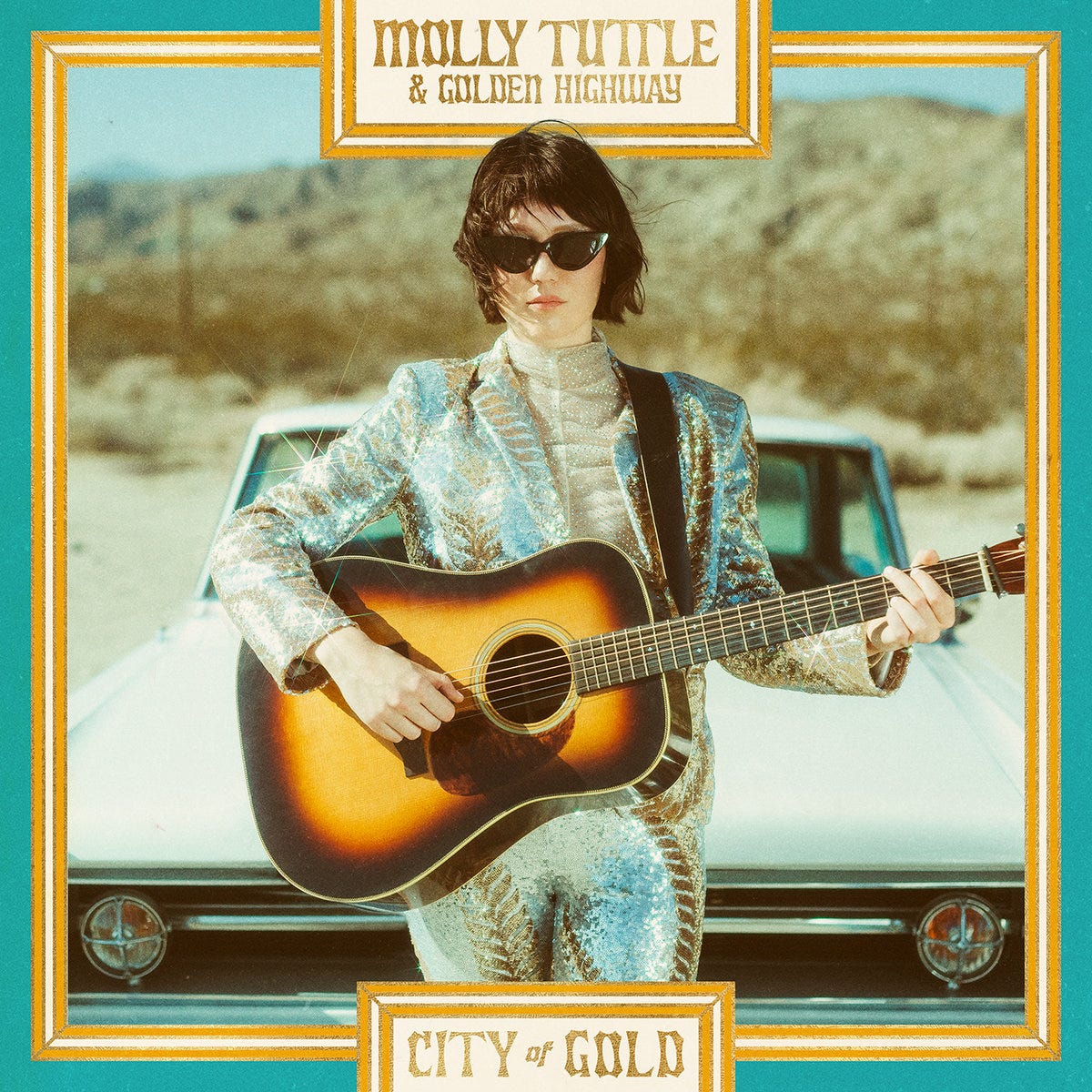

Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway - City of Gold

Molly Tuttle is in the zone— and I think she knows it. Always a proficient singer and guitarist, she struck a rich creative vein when she assembled her Golden Highway band, going full bluegrass for the rip-roaring Crooked Tree. Just a year later, she’s gathered the same musicians, producer, and songwriting partners for City of Gold, a companion album to Crooked Tree and on every level its equal. By this point it goes without saying that the album exhibits dazzling virtuosity: Listen to the breakneck pace at which Tuttle and Co. take the lickety-split ramble “San Joaquin,” or the graceful touch they bring to the ol’ soft-shoe number “More Like a River.” But what sets Tuttle apart is her gifting as a storyteller and conceptual thinker. City of Gold is loosely centered around the myths of the American West, and California in particular. She unfurls classic tales of boom and bust— industrious explorers who strike gold or who only find folly; those who are seduced by the freedom of the frontier and those brought low by its solitude. “El Dorado” is the perfect scene-setter, with Tuttle inhabiting the character of a Gold Rush madame who’s seen it all and lived to tell about it. The album highlight is “Yosemite,” where Tuttle and Dave Matthews duet as a struggling married couple hoping a trek out West will help them reignite their spark. (Opening couplet: “You said a road trip would do us some good/ Despite every instinct, I said that I would.”) As on Crooked Tree, Tuttle exhibits a knack for enlivening old-timey idioms with a contemporary point of view— not only in the feminist positioning of her Gold Rush Kate character but also in “Down Home Dispensary,” a bluegrass anthem for weed legalization. Tight harmonies, expert playing, imaginative songwriting, an eagerness to engage with tradition without being beholden to it— what’s not to love? With any luck, City of Gold will be part two in a long-running series.

Whitney Rose - Rosie

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Whitney Rose photographed without her broad-brimmed cowboy hat and a trusty pair of boots, a now-familiar getup that’s equal parts classic C&W and 90s arena country. That’s fitting for a traditionalist who favors classic honky tonk but isn’t above the occasional well-placed electric guitar solo, and whose music feels like a throwback without recalling any single era in particular. My favorite of her albums remains We Still Go to Rodeos, if only because it has her two most rousing songs— a Tom Petty-sized heartland rocker titled “I’d Rather Be Alone” and a loose, funny, Rockpile-inspired basher called “Better Man.” But Rosie, her first album since a brief health-related hiatus, sure ain’t bad; though more relaxed in its mood and tempo, it’s equally demonstrative of the breadth of Rose’s talents. “You’re Gonna Get Lonely” is the punchiest thing here, an easygoing honky tonk number with a raggedy piano breakdown. “Minding My Own Pain” is a sighing saloon song, while “Memphis in My Mind” gently rocks to a bluesy groove. These songs attest to Rose’s light touch, her casual command of roots music vernaculars, her preference for sturdy craft over showy production flourishes. Lyrically, she remains an astute observer of self-loathing: “My Own Jail” chronicles self-inflicted loneliness, while album standout “I Need a Little Shame” has a title that speaks for itself. No surprise: Rose’s moment of zen involves escaping to a “Honky Tonk in Mexico.” But boy am I glad she’s found her way back to making records.

Taylor Swift - Speak Now (Taylor’s Version)

One of my favorite albums of the year is Songs of Surrender, a sprawling collection that finds U2 revisiting songs from earlier in their career, reimagining some of their youthful compositions from the vantage point of age and experience. Sometimes this involves rewriting lyrics to reflect accrued wisdom, but just as often the shift in perspective is conveyed entirely through the changes to Bono’s voice. He doesn’t sound like he’s 18 anymore, and it’s affecting to hear how the passage of time has burnished his tone and phrasing.

You can hear a similar shift in perspective— albeit with a more condensed timeline— on Taylor Swift’s re-recorded version of Red, an album that imbues some of her best coming-of-age tales with added layers of wistfulness, distance, and regret. On the re-recorded version of Speak Now, however, there’s a level of remove from the original material that doesn’t work nearly as well. Perhaps that’s because Speak Now was always an album about youth, even its darkest and most rueful songs delivered with a girlish edge and the occasional tilt toward pettiness. A lot of that spunk has been sanded away from these recordings, not just because Taylor doesn’t sound as girlish anymore but because she’s taken a cue from Bono and rewritten some lyrics, notably removing a tasteless line from “Better Than Revenge” on the grounds that it wasn’t suitably feminist. But lapsing into tastelessness seems core to the teenage experience, while removing the line feels less like wisdom and more like brand management— evidence not so much of maturity but of Taylor’s evolving concern about how she’s perceived. None of that makes this a bad record in the least— Speak Now is still a wonderful example of state-of-the-art country-pop, “Dear John” is still one of her three to five best songs, the entire project of reclaiming her music is still totally admirable— but for the first time, I think Taylor’s Version is appreciably less potent and less necessary than the version we’ve come to know and love.

The Weakerthans - Reconstruction Site

Happy 20th anniversary to an album that meant a lot to me in high school and college— and remains in frequent rotation today. I can’t think of another album that more effectively marries highbrow poetry and intellectualism with emo-punk’s chunky guitar riffs and pummeling drums; it’s a perfect combo of headiness and crudity. The song about the cat wrecks me, and I’m not even a cat guy. At Stereogum, Keegan Bradford offers a great write-up, expressing why this music has proven so resonant and inspired such devotion.