Adventures in Listening, January 31 2023

Another gem from Joe Henry. Bill Berry returns. And: The White Stripes as performed by a Ukrainian wedding band.

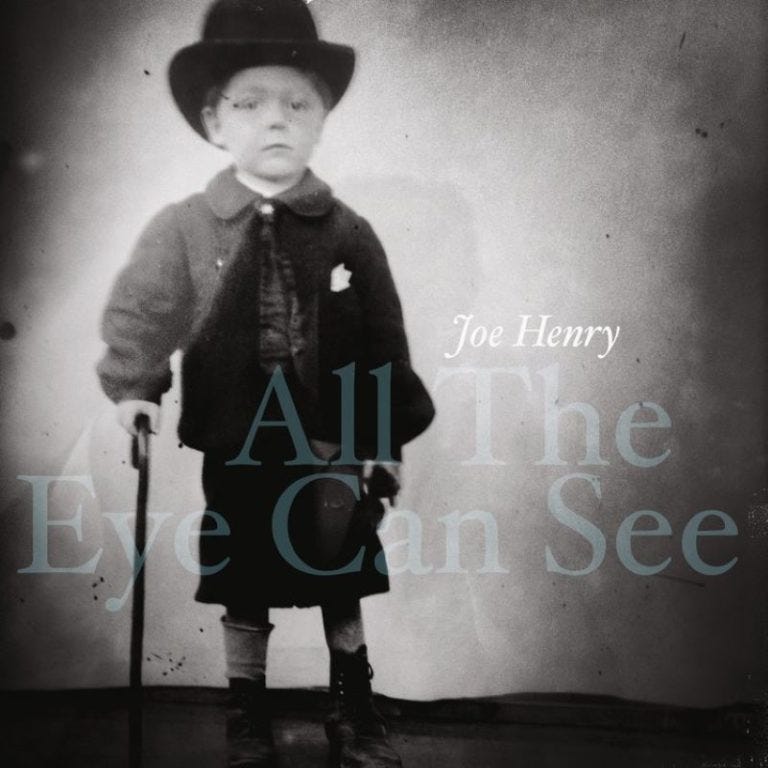

Joe Henry - All the Eye Can See

All the Eye Can See isn’t the first Joe Henry album to reckon with uncertainty as a prerequisite for vulnerability, brokenness as a catalyst for grace. Just four years ago, an album called The Gospel According to Water— released in the wake of a grim cancer diagnosis— extolled “the heart off guard, but ever open wide.” Joe’s now in remission, and his sixteenth album wrestles with an altogether different set of traumas— most notably our shared sense of dislocation in the wake of the global pandemic. It was recorded in quarantine, but, thanks to the magic of the Internet, it’s ironically his lushest, most orchestral work since 2001’s Scar. More than 20 musicians grafted their contributions onto Joe’s basic demos, among them boon drummer Jay Bellerose, master of atmosphere Daniel Lanois, and Joe’s son Levon Henry on sax and reeds. The guests who make the biggest impressions tend to be singers; I’m especially grateful for turns from Rose Cousins and Lisa Hannigan. For the most part this wrecking crew avoids scene-stealing solos, instead adding warmth and texture, accentuating Joe’s nakedly emotional melodies and rendering All the Eye the most romantic and inviting album in his estimable catalog.

Where the last couple of entries have exalted austerity, this one is caressed at every turn by a lush bed of strings and winds and voices. Generally speaking the music feels delicate, unabashedly pretty— though there are exceptions: “The Song I Know” channels Bertolt Brecht through Tom Waits, and “Small Wonder” reclaims a bit of the bluesy thump from Joe’s Blood from Stars era. Speaking of Waits, the clattering sound effects that rumble through “Karen Dalton” might have been rummaged from his vast sonic junkyard.

Over the past decade, Joe’s songwriting has increasingly eschewed linear, narrative lyrics in favor of more poetic abstraction. This has occasionally resulted in songs that feel like they dance around any kind of concrete particulars, but the writing on All the Eye Can See is emotionally acute, at times strikingly direct: “How did I think this story just my own?” goes one line, a humble acknowledgement of grief as equalizer. The best song, and immediately one for Joe’s greatest hits playlist, is “O Beloved",” which addresses the Divine in intimate and confidential terms, a la Rilke. (Joe’s also said the song was inspired by Little Richard; make of that what you will.) “Mission” pans out to take the long view of history, offering a scene of ash and ruin as the perfect place to rebuild and renew. “Yearling,” graced by doleful fiddle, is a tart confession of self-delusion, befitting the man who wrote “Sold” and so many others: “Angel of our mercy now/ Pull me close to thee/ And keep me safe from everything/ That tries to set me free.” “Pass Through Me Now”— its lyrics echoing Leonard Cohen’s truism that there’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in— seems like a perfect benediction, until Joe and The Milk Carton Kids offer an even better one with “Red Letter Day.” “Now’s the time,” they sing, and it strikes me that every moment of this wise, post-traumatic album can be captured in that simple adjuration: It’s as generous, beautiful, and affecting as any of Joe’s records, made to draw us together in our shared need, and suitable for playing like there’s no tomorrow.

Selo i Ludy Performance Band - “Sweet Seven Nation Dreams”

I’m sure I wasn’t the only reader to register some surprise when Robert Christgau— the famously scrupulous critic whose practice extends back to the 1960s— named the Selo i Ludy Performance Band to his Album of the Year slot. The Performance Band is a very workmanlike all-covers troupe, the kind of band you’d sooner encounter at a wedding venue than at a proper club, and their independently-released Bunch One includes ingratiating, ragged covers of karaoke classics from R.E.M., A-ha, and Alice Cooper, among others. It’s charming despite (or maybe because of) a thin, self-produced sound and a modest scope, played with plenty of vigor and good cheer; and if it’s hard to critically justify such a humble collection topping benchmark albums from Beyonce and Big Thief, it’s to Christgau’s credit that he doesn’t really try. (Surely there is a general Ukrainian goodwill in effect, and that’s a perfectly fine reason to celebrate an album like this.) I’ve played it a few times now and agree that there’s something weirdly touching about hearing these low-culture totems performed with such unfussy, unpretentious glee, cherished the way some of us might cherish the Great American Songbook. The entire half-hour record is worth your time, but if you just want to sample something, I’m especially fond of this White Stripes/Eurythmics mash-up. If nothing else it begs the question: Given that Jack and Meg made an album full of marimbas, why did they never do the same for the accordion?

The Bad Ends - The Power and the Glory

Nowhere on my 2023 bingo card do I see a space for Bill Berry’s return to action, but with the debut album from The Bad Ends, that’s exactly what we get. Berry— the stalwart drummer whose steady swing brought classic-era R.E.M. their propulsive force— retired in the mid-90s after being sidelined by a brain aneurysm, trading his drum sticks for farming implements. The band’s subsequent albums mostly sounded lethargic, wanting for Berry’s mighty whallop, but The Power and the Glory scratches the itch for anyone who feels like the IRS years were where R.E.M. peaked, sounding a bit like it could have come between Lifes Rich Pageant and Document. Berry is joined here by Mike Mantione, something of a local legend within the Athens, GA music community, and together they’re released an unabashed jangle-pop revival, relying on familiar sounds just enough to make the few curveballs (a tender instrumental called “Ode to Jose,” a garage-rock melodrama called “The Ballad of Satan’s Bride”) really pop. But to say that this album makes it seem like no time at all has passed since R.E.M.’s 80s heyday isn’t quite right: The dark subtext to these songs is that if anything time’s passing too quickly, and as an album highlight called “All Your Friends are Dying” makes plain, nostalgia’s not gonna save anyone.

Peter Gabriel - “Panopticom”

Peter Gabriel’s So was one of the first albums I bought with my own money, and has been a staple of my desert island list ever since. I’d long given up hope that we’d hear any substantial new music from him, now more than two decades removed from the enigmatic Up, so the very existence of “Panopticom” registers as a welcome surprise. I’m less enthusiastic about the song’s tech-optimist subject matter— Gabriel says it’s about his idea “to initiate the creation of an infinitely expandable accessible data globe,” and I am faintly reminded of those Microsoft commercials where Common tries to convince us that AI will be a net-positive for humanity. Ignore the lyrics and you can appreciate the song’s light touch: Not only does Gabriel’s voice sound as strong and clear as ever, but the band locks into a perfectly pleasant groove. Given its long gestation, this material doesn’t sound particularly overwrought or fussed-over, which makes me hopeful that the upcoming i/o album— I’m now about 80% sure it’s actually going to see the light of day— will be worthwhile.

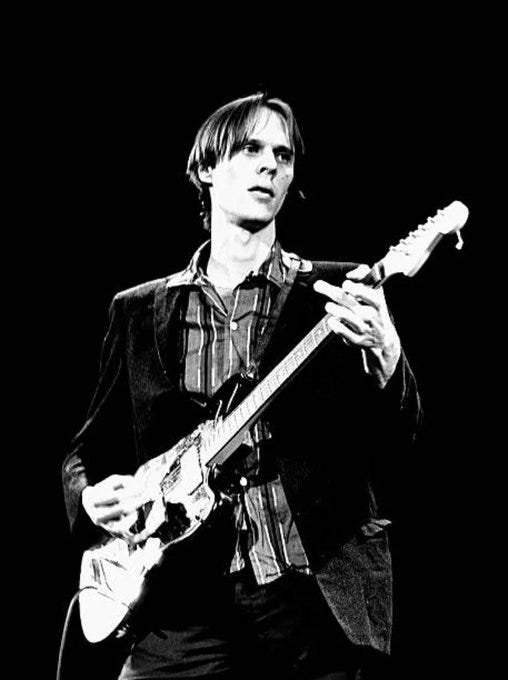

R.I.P. Tom Verlaine

For as long as I can remember I’ve daydreamed of being a drummer. When the other kids fantasized about preening and crowing like Bono or Mick Jagger, I just wanted to make it thunder and rain like Elvin Jones. But all that goes out the window when I hear the electric thrum of Television, whose Marquee Moon I consider to be the greatest guitar album of all time. That’s obviously in no small part due to Tom Verlaine, whose exacting solos influenced my taste nearly as much as his sneering demeanor and metropolitan poetry. Verlaine died last week at 73, and Christgau offers a more knowledgeable eulogy than I ever could.