Adventures in Listening, June 30, 2023: No Plan B

Two of the year's most substantial, exhilarating new records come from Black women working at the top of their game: A soul revue from Bettye LaVette and a funk odyssey from Meshell Ndegeocello.

Bettye LaVette - LaVette!

One of my favorite albums of all time is The Scene of the Crime, the 2007 masterpiece from legendary soul singer Bettye LaVette. Though nine out of its 10 songs are covers, the album has always struck me as a sharp work of autobiography; to paraphrase something Stephen Deusner wrote about a different LaVette record, she has an uncanny ability to rewrite other people’s material simply by singing it. Working with classics by Elton John, Ray Charles, and Willie Nelson, among others, LaVette used The Scene of the Crime to sketch a redemptive arc through failure, struggle, poor decisions, perseverance, and vindication. It’s an arc remarkably similar to her own.

It’s notable, then, that she’s named her new album after herself, never minding the fact that all 10 of its songs were penned by Randall Bramblett. The implication is that this is no mere tribute album, but rather another exercise in self-discovery and self-mythologizing that just happens to lean on somebody else’s words. LaVette’s work here earns the self-referential title, and it earns its exclamation point, too. This is not just her best album since The Scene of the Crime but the one that bears clearest witness to her astonishing gifts as an interpretive singer. Through actorly phrasing and magnetic presence, she inhabits these songs as though they were her own memoirs.

LaVette! was produced by the drummer and honorary Rolling Stone Steve Jordan, who also helmed the superb Blackbirds and the freewheelin’ Dylan revue Things Have Changed. I have occasionally found his work to be a little too slick, particularly relative to LaVette’s soulful rasp, but this is the album where artist and producer really seem to click. Working alongside session pro (and D’Angelo sideman) Pino Palladino on bass, Jordan provides a supple foundation for songs that cross-pollinate blues, gospel, country, and rock— a milieu that honors Bramblett’s genre-agnostic southern style while also playing to LaVette’s omnivorous strengths. As ever, she is pure electricity on the uptempo numbers: She makes a meal of the rumbling polyrhythms on “Hard to Be Human”— equal parts grimacing funk and frenzied afrobeat— and she rampages through “Don’t Get Me Started,” backed by a carnivalesque organ played by Steve Winwood. (Side note: I feel like I’ve waited my whole life to hear LaVette open a song with “don’t get me started…”) When the tempos slow, she stretches out syllables to wring maximum emotion: Check the weepy country tearjerker “I’m Not Gonna Waste My Love on You,” or the percolating southern simmer of “Lazy (And I Know It).” Jordan elevates these recordings by calling in exemplary session musicians who play with both professionalism and personality, including a brief but memorable Jon Batiste piano solo on “Mess About It.”

What makes LaVette a major artist— and I do consider her to be one of our most significant singers and record-makers— is the way she excavates depths of meaning from every song, tearing into the text and subtext alike. If you know anything about her personal struggle— decades spent being chewed up by the record industry before a triumphant comeback in her 50s— then you’ll be moved by “Lazy (And I Know It),” a rejection of ambition on the world’s terms, but an assertion of the singer’s own high standards. Bramblett’s writing can be funny and existential, cocky but also self-reflective, which is to say that he’s well-suited to be LaVette’s muse. She turns his “Plan B” into an anthem for anyone who feels like they were born to do just one thing, and won’t accept anything less than their God-given vocation. LaVette! proves again and again that she’s doing what she was made to do, and at a higher level than just about anyone else in her field.

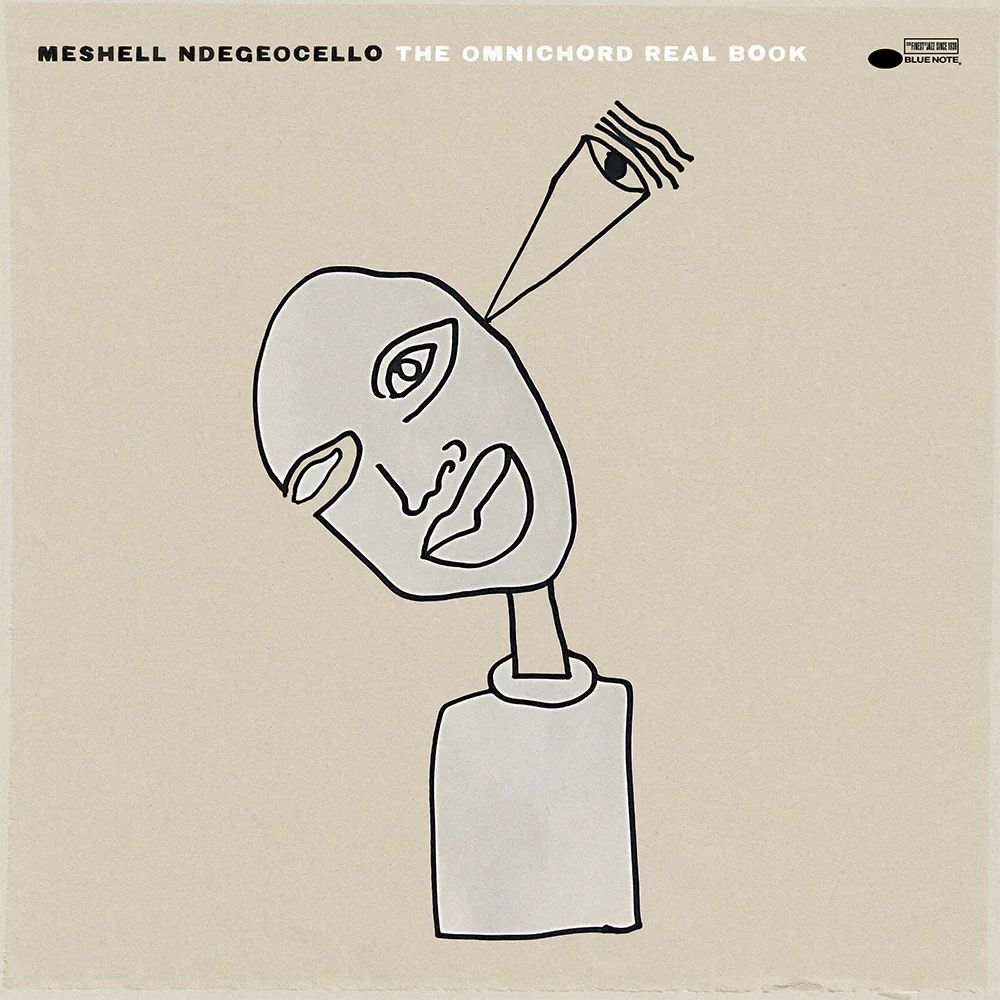

Meshell Ndegeocello - The Omnichord Real Book

“Please take control,” goes one of the songs on The Omnichord Real Book, new from Meshell Ndegeocello. It’s a line pitched somewhere between a plea and a prayer, and it presents a theme that recurs, in various configurations, throughout the album— the illusion of control, the loss of control, the willful surrender of control. Ndegeocello wrote this album at least partly in response to the death of both her parents, so it seems fair to say that she’s reckoning with the notion of self-sovereignty as a way of acknowledging that she never really had any. A song called “Towers” isn’t about the beautiful edifices she’s built in her life, but rather about their unexpected collapse: “Remember the day it all came crashing down?” But what’s most striking to me about Ndegeocello’s venture into the wild unknown is how she sounds so serene— dare I say liberated— to have her illusions of control stripped away. “Be at peace within the chaos,” goes another line. The Omnichord Real Book more than lives up to that advice.

Ndegeocello has done a little bit of everything in her career, from hip-hop to torch songs, and it might be easy to assume that her album about surrender might coincide with a foray into jazz— a music known for its freedom and and its exploratory nature. It’s an assumption that’s seemingly validated by her new affiliation with the storied Blue Note label, and by the album’s deep bench of top-shelf jazz performers— among them pianist Jason Moran, vibes master Joel Ross, and harp virtuoso Brandee Younger. Ndegecello plays the role of visionary and band leader, anchoring the album with her electric bass playing and often stepping into the spotlight to sing, but just as often ceding space to her wild cast of collaborators. But while there’s a sense of discovery here that conjures the spirit of jazz, I think Nate Chinen is right when he says the music is just as jazz as you need it to be: It would be just as apt to say that The Omnichord Real Book is a funk odyssey, finding space for rumbling grooves, delicate singer/songwriter fare, spacey explorations, frenzied afrobeat, and more. (Incidentally, the omnichord is a kind of hand-held drum machine of 1980s vintage, a jumping-off point for these new compositions but only audible in three or four of them; further evidence of the album’s unfettered, going-where-the-spirit-leads ethos.)

In fact, I’m ready to declare The Omnichord Real Book one of the most freewheeling, adventurous albums in recent memory— an album where it’s genuinely thrilling to hear how the artist follows one left-field surprise with another, but also an album where everything holds together through shared spirit and emotional through-line. The undeniable funk masterpiece is “Virgo,” a magnificent space-age journey that builds from Ndegeocello’s taut bass line to the celestial glow of Younger’s harp; at almost nine minutes it’s the album’s clear centerpiece, its yearning for the stars articulating a desire for transcendence that other songs leave simmering under the surface. The other big set piece is “Burn Progression,” where two alternating refrains— “things fall apart” and “oh happy day”— convey the paradoxically liberating nature of lost control; as if to prove its own point, the song spirals into a blissful drum-n-bass breakdown. These are merely two of the album’s most major constructions, yet I find just as much pleasure from Ndegoecello’s simpler confections: Nothing on the album delights me more than an irresistibly featherweight instrumental called “Omnipuss.”

Throughout the album, Ndegeocello’s songwriting radiates outward through different Black music tributaries, guided by her discoverer’s zeal and her bruised, reflective posture. For singer-songwriter fare, try “Gatsby,” an aching hymn to failure and self-delusion. For afrobeat, check the blazing, bass-heavy “Vuma.” I’m not sure what to say about the gritty funk of “Clear Water,” except that it feels almost like a lost Sly Stone original. These songs all lead inevitably toward “Hole in My Bucket,” a children’s song about mending something that’s badly busted, performed with earnestness and candor by an acapella group called The HawtPlates. The finale is a brassy remix of “Virgo,” with blustery horns arranged by jazz legend Oliver Lake— one last adventure into the great unknown.