Adventures in Listening, March 30, 2023: Pass the Plugs

The De La Soul catalog is finally available on streaming platforms, restoring a seminal chapter in hip-hop history. Plus: A disruptive new hardcore album from Zulu.

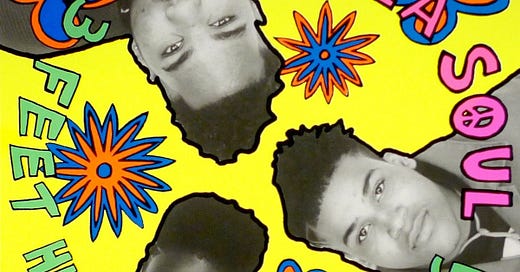

De La Soul - Complete Discography

I still have my CD copies of the first two De La Soul albums, 1989’s 3 Feet High and Rising and 1991’s De La Soul is Dead; their absence from the streaming services lo these many years is one of the best arguments I can think of for holding onto your physical media. For those who aren’t preppers, hoarders, or geriatric millenials like me, the entire De La Soul catalog has made it onto God’s internet at last, following years of legal rigmarole over samples clearances and copyright issues. It’s unlikely that there will be a more consequential streaming debut all year. In fact, the newfound availability of these albums means that younger hip-hop enthusiasts can finally catch up on one of the genre’s more crucial and rewarding chapters. It’s no exaggeration to say that a critical piece of hip-hop history has been restored to the narrative, recentered in the canon.

To commemorate the digital release of these albums, superfan Questlove shared a series of Instagram videos, wherein a number of Black luminaries— artists and thinkers as diverse as Maya Rudolph, Chuck D, and Chris Rock— offered their own De La Soul testimonies. What was notable to me was how many of these testimonies credited De La Soul with validating the diversity of Black experience, making it okay to express Black culture and pride in unconventional ways. The sense I get is that these albums created a kind of Wakandan embassy for Black nerds, theater kids, comedy geeks, hippies, and nonconformists. (Notably, a video from Bill Hader speaks to the breadth of De La Soul’s influence, affirming the impact their album concepts and skits had on his taste for comedy. Another video, from Damon Albarn, suggests international appeal.) I’m not Black but I do care about hip-hop, and when I heard these albums for the first time I was struck by how they engaged with the genre’s long-standing obsession with “authenticity,” but defined that concept according to a different set of values— not tough-talk, sociopolitical realism, nor even technical virtuosity, but rather whimsy, surrealism, and imagination. These values pointed True North on the De La Soul compass, and it was by following them that the group remained most authentically themselves.

If you’re coming to the De La Soul canon for the first time, I recommend starting at the beginning. 3 Feet High and Rising is rightly venerated as a classic, a kaleidoscopic celebration of bright colors and cheerful humor. (As a testament to the album’s non-confrontational spirit, I note that only one of its 23 tracks bears an explicit language warning.) The album opens with an absurdist game show sketch, attesting a group that’s as deeply influenced by Monty Python and SNL as they are their rap forefathers, and they return to that conceit throughout the record, animated by a boyish camaraderie: To me the great pleasure of this album has always been in hearing a group of friends sounding totally secure in their shared sense of humor, creating a tapestry of in-jokes and reference points with no objective other than to make each other laugh. Their flair for silliness set them apart from their peers but also distinguishes them from their disciples: Nobody stans for De La Soul like The Roots do, and yet it’s impossible to imagine The Roots allowing this kind of levity onto their their very earnest, increasingly sober-minded records. (They save their silliness for The Tonight Show, I guess.) Their whimsy can almost disguise their zeal for invention, their technical prowess. Thanks to producer Prince Paul, 3 Feet is a smorgasbord of clever samples, and the trio’s tag-team rapping is nimble and energetic. You’ll hear many of their greatest hits on this album (“The Magic Number,” “Potholes in My Lawn,” “Buddy,” “Me Myself and I”), but my low-key favorite is “Can U Keep a Secret,” wherein the De La guys just whisper gossip about each other over a clattering beat. Its total commitment to a silly premise is exactly the kind of thing I found hilarious in high school, and still find funny today.

The success of 3 Feet High and Rising brought some unintended consequences: Namely, De La Soul felt pigeonholed as hippies or goodie two-shoes, an image they were eager to shed with De La Soul is Dead. This is the point where you’ll hear their good vibes start to curdle, something that’s evident from the album’s unifying concept— basically a series of increasingly violent and cynical skits about how nobody likes De La Soul anymore, the caustic humor closer to I Think You Should Leave than to Monty Python. I think this album is their masterpiece, not least because its the best example of De La Soul uniting hip-hop technique, standup comedy chops, and ace studiocraft to make something truly original and weird. My favorite De La Soul tracks are on this album: A tongue-twisting, Tom Waits-sampling groove called “Oodles of O’s,” a slice of roller rink euphoria called “A Roller Skating Jam Named ‘Saturdays,’” and best of all “Pease Porridge,” where the De La guys deflate their own mythos over a strange, addicting mashup of nursery rhyme chants and rattling percussion. By shredding their good-vibes-only reputation, they also free themselves to write candidly and sensitively about serious issues: “My Brother’s a Basehead” is self-explanatory, and “Millie Pulled a Pistol on Santa” is a harrowing song about abuse— one of the most incisive pieces of writing in all of hip-hop. The album is wall-to-wall genius, bleak humor, and musical sophistication— perversely stitched together by chatter about how whack De La Soul is.

My most basic and boring De La Soul take is that their first two albums are their best. The music that came after has plenty of value— I know some galaxy-brain critics who advocate for Buhloone Mindstate as their magnum opus, and the title track to Stakes is High remains one of their signature songs. (To uncover some deep cuts, check out this roundup from Nate Patrin.) For me, the music made past De La Soul is Dead is often too insular and too grim in its assessment of hip-hop culture, and of De La Soul’s place in it. Yet taken as a body of work, the De La Soul catalog remains exciting, inventive, and one-of-a-kind, as essential as the discographies of A Tribe Called Quest, The Roots, Gang Starr, or Public Enemy. If you’ve never spent any time with this group, a treasure trove awaits you— more accessible than ever before.

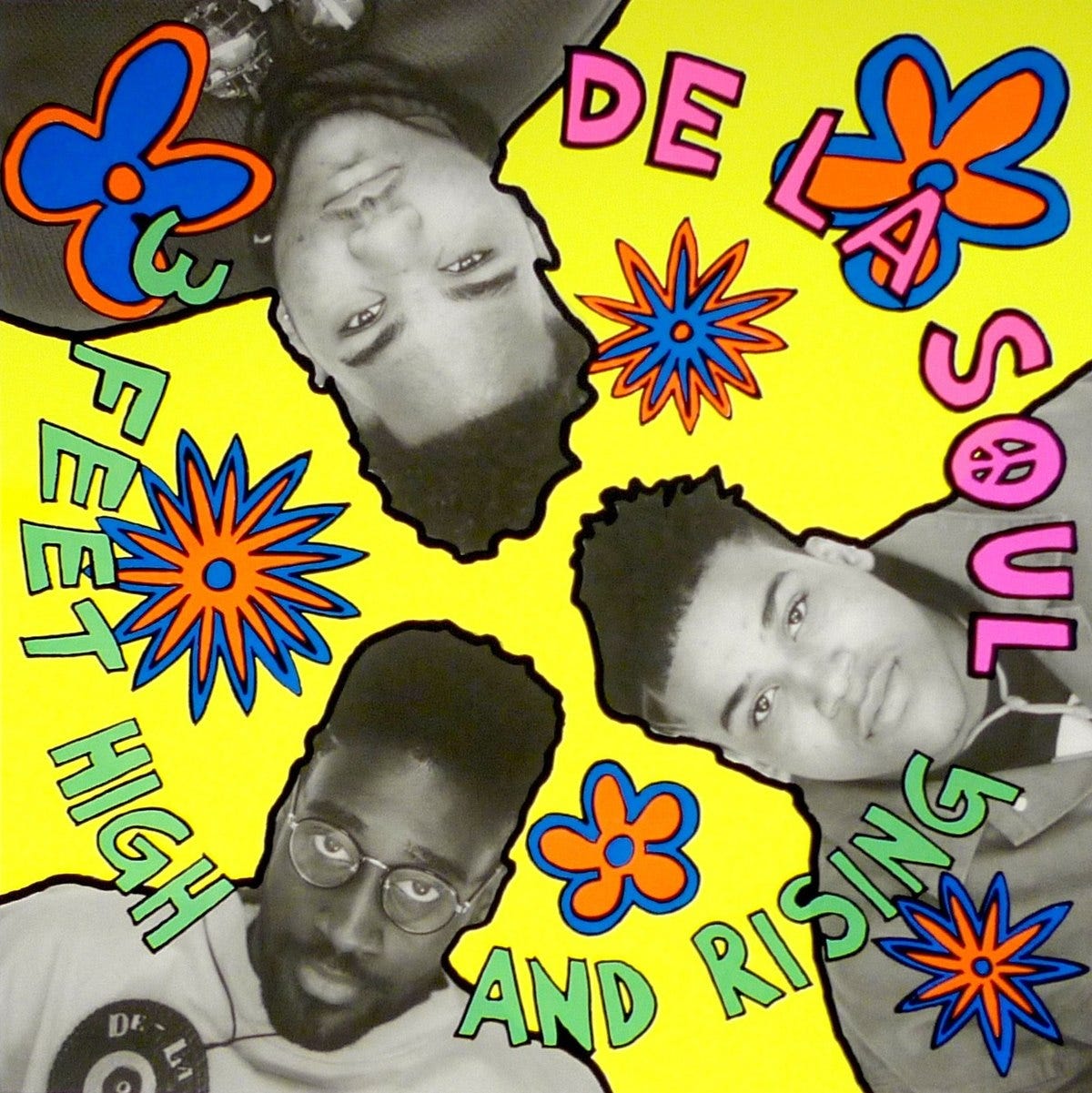

Bono & The Edge: A Sort of Homecoming with Dave Letterman

U2 has never done anything on a small scale. Remember the iTunes thing? Even their new Songs of Surrender collection, which foregrounds intimacy and simplicity, feels ambitious in its 40-song sprawl. That makes the deliberate modesty of their Disney+ documentary feel fairly unique within their oeuvre— and fairly charming. There’s nothing grandiose about it: With their two bandmates temporarily sidelined or unavailable, Bono and The Edge rent out a little theater in Dublin to perform stripped-down arrangements of their hits, basically in the vein of the Songs of Surrender reimaginings. They invite their old pal Dave Letterman to toddle around Dublin, conduct some one-on-one interviews, and emcee their show. There is a little bit of U2 hagiography involved, but for the most part the film allows us to forget that they are superstars and instead see them as neighborhood kids made good. At one point Edge says that they still have all the same friends they had when they were 16, and it feels entirely credible; when Glen Hansard shows up to sing with them, it might as well be one of Bono’s pub buddies dropping by for an impromptu hang. The involvement of Letterman is critical to the success of this movie, not only because he is a funny and garrulous host, but because he asks some genuinely probing questions about the role of religion and geography in U2’s formation. All of this adds color and context to the band’s other recent retrospectives (the album and Bono’s Surrender memoir), but even if you don’t care about any of that, there’s plenty of lovely, arresting music. Most compelling of all is a rousing, full-throated take on “Invisible,” an overlooked song that the book, album, and film all recenter as an essential anthem within the U2 catalog— a reappraisal that’s completely validated here.

John Lee Hooker - Burnin’ [Expanded Edition]

John Lee Hooker’s music is usually conceived as something fairly primitive— a music of stomped-foot percussion and droning, single-cord boogies. Charles Shaar Murray, in his excellent book Boogie Man: The Adventures of John Lee Hooker in the American 20th Century, makes a compelling case for Hooker as consummate modernist, an infinitely adaptable musician who was always game to retrofit his music into the prevailing style of his era, capitalizing on the “folk revival” on one record, incorporating Latin beats on the next. Released in 1962, Burnin’ would have been considered a fairly state-of-the-art blues album for its day and age, with Hooker adapting an urbane, R&B-influenced sound. It’s not dissimilar to contemporaneous records from, say, B.B. King, yet it could just as easily fit on the shelf beside a Ray Charles album. Hooker’s backed by a crack studio band, including two sax players and the Motown rhythm section, and together they create an elegant, after-hours sound that’s about as pop-minded as Hooker ever got. Purists might recoil at this, as there’s relatively little space for Hooker to get lost in extended guitar boogies— the songs are short, and he has to share space with those horn players— yet at the same time, it’s amazing how much Hooker sounds like Hooker in what could have been a relatively anonymous setting. The big hit from this album is “Boom Boom,” a perfect snapshot of Hooker’s economical songwriting and pop smarts, but I’m nearly as smitten by “Let’s Make It,” the album’s most rambunctious, locomotive groove. For something slower, check Hooker’s unflappable, almost disdainful delivery of “Drug Store Woman.” The whole thing is great, and it’s available now in a a handsome re-issue. Though the bonus material is minimal, you’ll get both stereo and mono mixes that sound crystal-clear. And incidentally, if you do want the more down-home Hooker, chase this one with 1960’s acoustic That’s My Story, which is also top-notch.

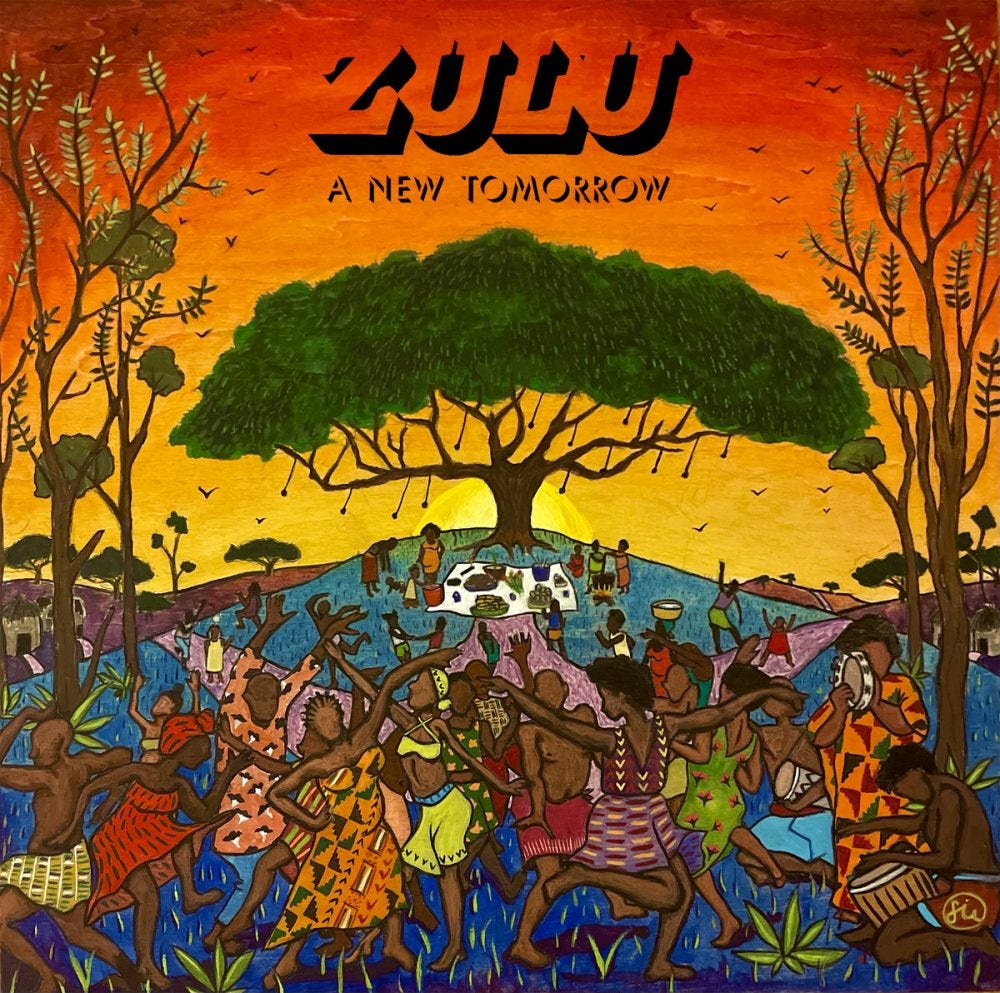

Zulu - A New Tomorrow

My favorite hardcore albums are all about seamless pacing, masterfully controlling the ebb and flow of physical energy. A New Tomorrow, the debut album from Los Angeles crew Zulu, flips the script, offering a sequencing that’s deliberately jagged and disruptive. The group blasts through some of the loudest, hardest, most punishingly aggressive music you’ll hear all year— and then, just when the songs reach peak intensity, they abruptly shift into quieter stretches, featuring extended samples of soul and reggae luminaries from Nina Simone to Curtis Mayfield. It’s a bewitching marriage of punk aggression with hip-hop’s historical curation and recontextualization. And, it all leads somewhere: Toward the end of this 28-minute album, the raging guitars cede space to delicate piano, while spoken-word poetry laments the reduction of Black life to struggle: “Discourse around Blackness in America often orbits around Black pain… but I grow weary of repeating our plight/ While never highlighting the beauty of us.” It’s heartfelt and convicting, but more than that, it’s illuminating to what this band is up to with the range of samples and textures that populate this record. It’s not always an easy listen, but it’s deep, smart, and disruptive in all the right ways.