Adventures in Listening, May 16, 2023: Seconds of Pleasure

Jessie Ware offers disco delights, while The National mines middle-aged malaise. Plus: Lonnie Holley remembers everything.

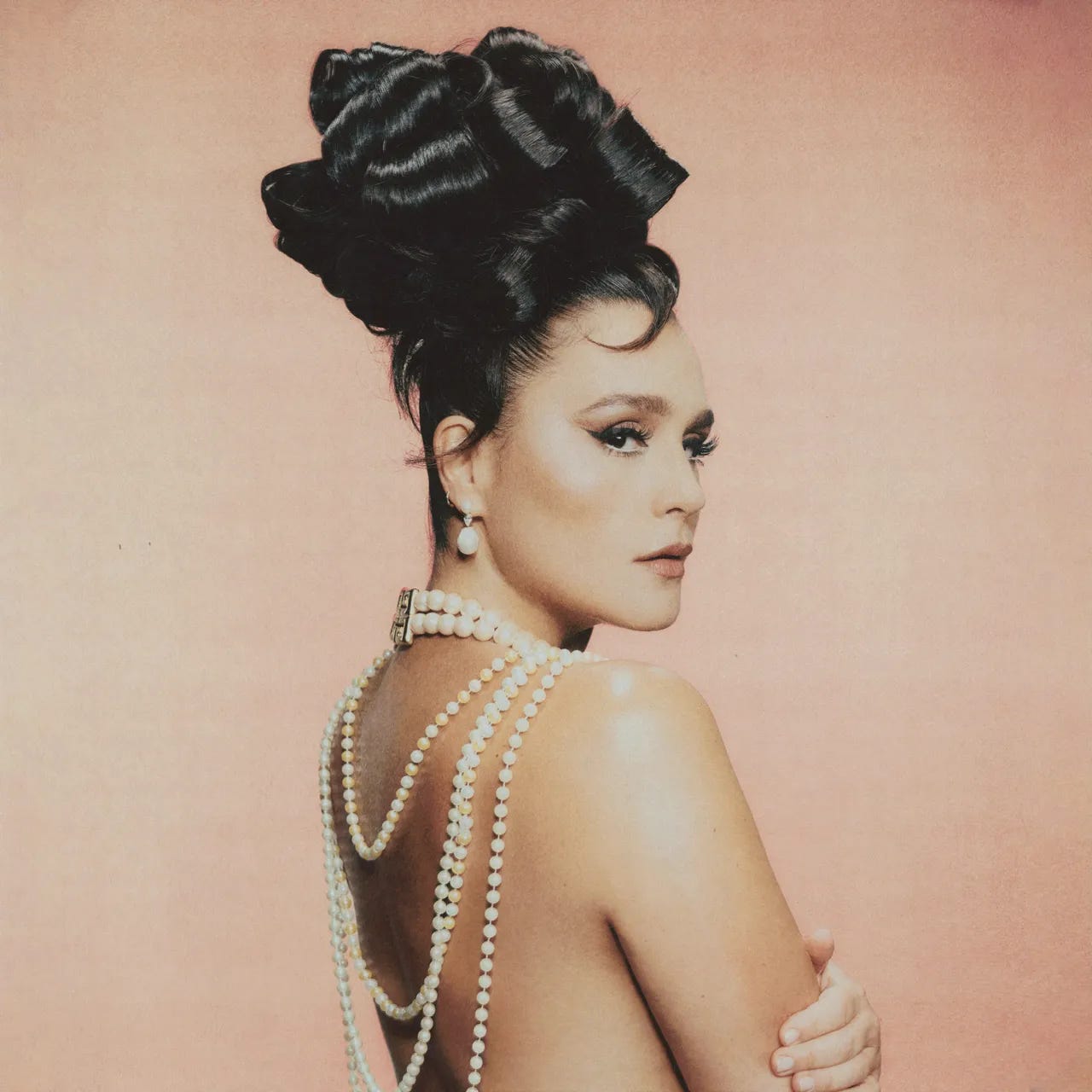

Jessie Ware - That! Feels Good!

Although the new Jessie Ware album pays homage to any number of classic disco records from the 70s and early 80s, the reference point that looms largest is of a much more recent vintage. That would be Beyonce’s Renaissance, last year’s critically-acclaimed excavation of club music— an album so universally beloved that I almost feel bad for Ware having to occupy the same sonic lane. Actually, the albums are dissimilar in many regards— Beyonce’s record casts a wide historic net, its liner notes just as mind-expanding as the music itself, while Ware zeroes in on the more specific, full-band sound of bands like Chic— but what they share is significant: A full-bodied embrace of the dance music ethos, addressing the anxieties of our present age by upholding physical release as a kind of personal liberation. To that end, Ware’s songs exhort us to get moving, to get free, to seek pleasure, and if something feels good, to do it again and again. Nearly every song is ostensibly about moving your body on the dancefloor but might really be about moving your body in the bedroom; by sticking to simple invitations and admonishments, Ware’s songwriting serves as a gentle caution against the dangers of overthinking everything. (Also worth noting: Without a single track flagged as explicit, this is an album that keeps its carnality at least somewhat subtextual, to charming effect.) If the record lacks the genre-spanning ambition of Beyonce’s, it matches it in terms of sheer, uncomplicated joy and exuberance. With regard to writing and craft, these songs all sound like they should be hit singles, from the piano-pounding anthem “Free Yourself” to the ecstatic release of “Pearls” to the sing-along empowerment anthem “Begin Again.” And as a singer, Ware has found the place where she really shines, and she is crushing it. Tremendously fun and physical, That! Feels Good! provides plentiful pleasure of its own.

The National - First Two Pages of Frankenstein

The poet laureates of middle-aged malaise return with a new album of exquisitely sad songs, chronicling personal disappointment and romantic dissolution with a wistful sigh. This is a band that found its lane a long time ago and seldom veers out of it, which means that First Two Pages of Frankenstein probably won’t do much to change your opinion of them. It’s a testament to their high level of craft that they can still find fresh variations on familiar themes, sometimes writing songs so quintessentially The National that it’s amazing they didn’t already exist. A case in point is “Eucalyptus,” which finds Matt Berninger creating a literal inventory of loss— defeatedly relinquishing custody of all the things he’s decided he can live without. Berninger remains an iconic and perfectly-cast singer, his weathered, creaky sigh the optimal instrument for The National’s dashed dreams. And as a lyricist, he remains a wonderfully articulate mouthpiece for emotionally inarticulate men. (Sample phrases: “I was suffering more than I let on;” “there’s nothing stopping me now from saying all the painful parts out loud.”) He’s at his best when the songs push back at him a little bit, forcing him to put up a fight: With its kinetic pulse and maelstrom guitars, “Tropic Morning News” is easily the most instantly likable thing here, with the rumpled dishevelment of “Grease in Your Hair” coming in a respectable second. Some of the other songs have a little too much give, rendering Berninger’s resignation as just another gloomy texture, tasteful in all the ways you don’t necessarily want a rock band to be tasteful. As for the Taylor Swift crossover audience, skip straight to “The Alcott,” a bittersweet waltz that would’ve been third-tier on Folklore, but a highlight on Evermore.

Lonnie Holley - Oh Me Oh My

Now 73 years old, the singer and painter Lonnie Holley still has vivid recollections of growing up in Jim Crow-era Birmingham— and they all come rushing back to him on Oh Me Oh My, his magnificent new album. The record plays less like a carefully-organized memoir and more like a bleary, free-associative string of loose memories, stray details, and feelings he’s held on to since childhood, all tempered by decades of accrued wisdom. It’s heady stuff, but also exhilarating; in fact, it’s the most accessible music Holley’s ever made, and only in part because he has a murderer’s row of indie-rock singers to lend harmony to his gravitas. (Bon Iver does the typical Bon Iver thing, but I’m much more excited about hearing the solemn intonations of Michael Stipe.) The music alternates between slow, tranquil meditations and rapturous, mystic grooves, with the latter sounding particularly inviting: Working with the poet and jazz conjurer Moor Mother, Holley creates an ecstatic groove across “I Am Part of the Wonder,” complete with skronking sax, skittering percussion, delicate kalimba, and slinky bass. “Mount Meigs",” named for an “industrial school for Negro children,” is considerably more ominous, Holley’s haunted memories roaring like thunder. Oh Me Oh My bears witness to considerable pain but also to grace, strength, and survival: It’s an open-hearted and beautiful record wrought from a troubled history, and its redemptive power is unmistakable.

Taj Mahal - Savoy

On paper, this sounds like exactly the kind of thing I’d be into: An elder statesman of the blues, paying homage to a famed Harlem nightclub through a series of brisk big-band performances, hitting on standards from the likes of George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, and beyond. And yes, there is something charming about hearing Taj creak and growl through these otherwise smooth performances, often buffeted by a chorus of female harmony singers. But small pleasures of musicianship don’t obscure the fact that this album is a fairly one-dimensional exercise in nostalgia. Whereas albums like Allen Toussaint’s The Bright Mississippi or last year’s Taj/Ry Cooder team-up Get on Board revitalize standards with a palpable sense of discovery, Savoy feels more inclined toward recitation, as though the album is conceived as a way to replicate Taj’s childhood memories of this music as faithfully and reverentially as possible. That hardly makes for an unpleasant listen, but I’m just left wondering why in the world we need still another dutiful version of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside”— complete with winter wind sound effects!— or how many times “I’m Just a Lucky So-and-So” can be performed with the same old-time showbiz swagger. This may be a worthwhile testament to Taj’s skill as a big band leader, and to the enduring tunefulness of the old Savoy songbook, but it does little to make its historical era feel alive or contemporary.