All Smiles

For a time, both Radiohead and Coldplay seemed like viable contenders for the British rock crown. Recent albums reveal how widely their paths diverged.

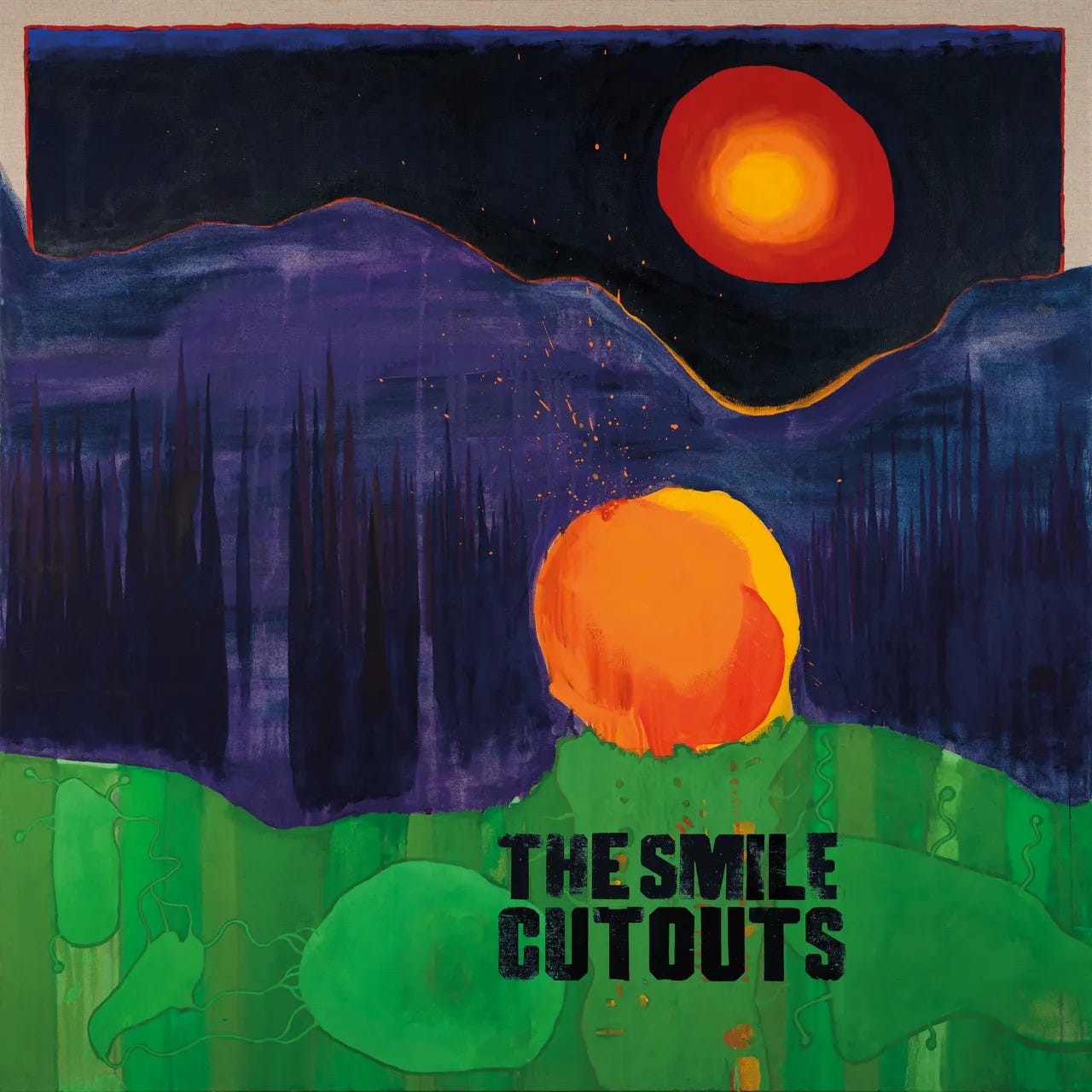

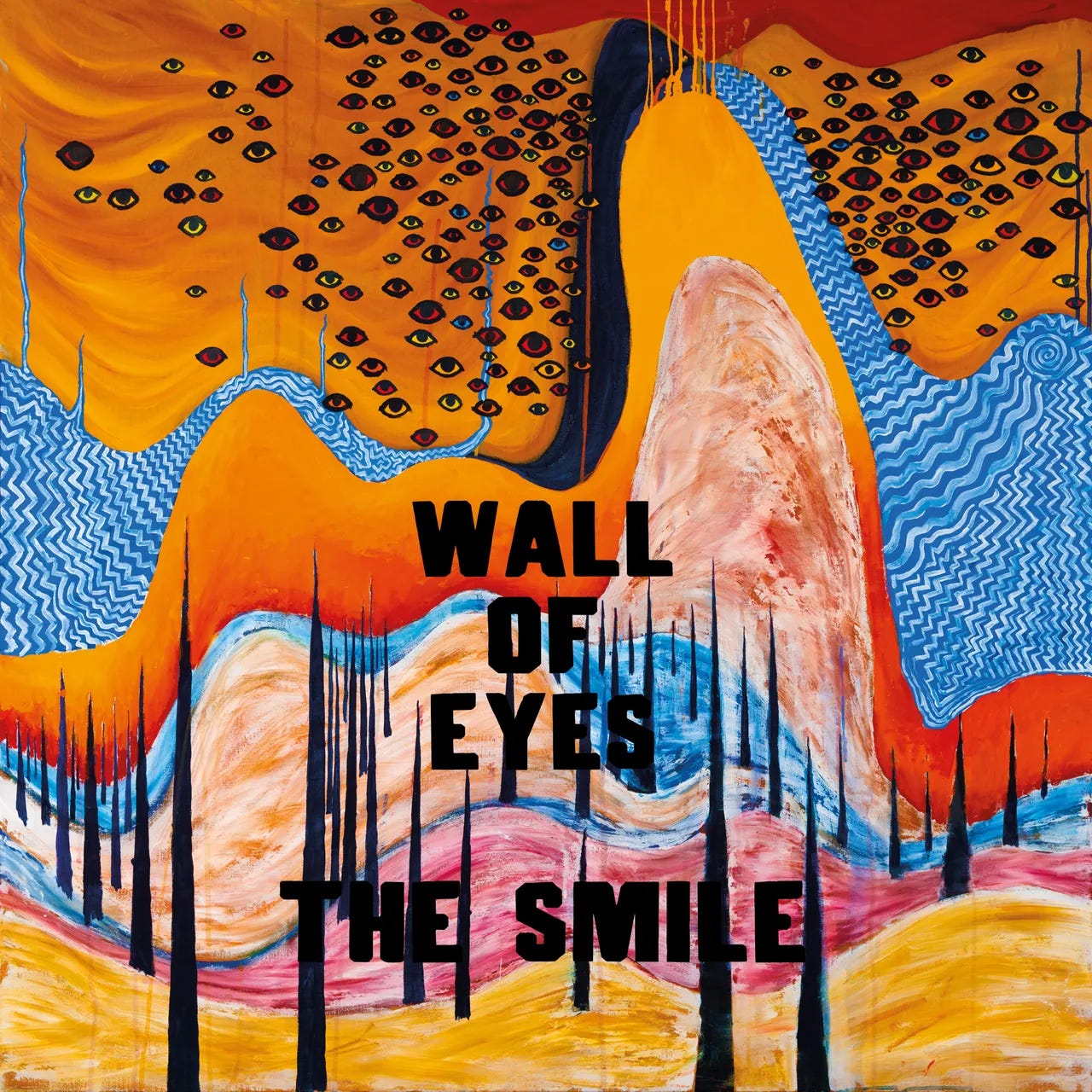

The Smile - Wall of Eyes/ Cutouts

When Radiohead released their seminal album Kid A in the fall of 2000, it was widely heralded as a zeitgeist-defining masterpiece— an album where fractured electronics conveyed prophetic meaning about the dehumanizing effects of technology. Of course, not everyone heard it that way. In a memorable review, alongside a not-bad-at-all rating of A-, the critic Robert Christgau wrote, “Alienated masterpiece nothing— it’s dinner music. More claret?”

Far from being a flat dismissal, Christgau’s sentiment created a permission structure for listeners who were uninterested in the sociopolitical meaningfulness of Thom Yorke’s lyrics, but wanted to enjoy the album on a different set of terms— savoring its moody majesty, its grim beauty, and its textural richness. It’s a sentiment that proves handy for engaging the work of The Smile, the Radiohead offshoot that, since 2022, has proven a surprisingly prolific vehicle for Yorke and his long-time colleague Johnny Greenwood, allowing them to make music while their main band remains paralyzed by its own legacy.

Yorke and Greenwood are joined by Tom Skinner, a veteran jazz drummer who has also worked with the likes of Shabaka Hutchings and Nubya Garcia. Together, the trio has released three fine albums, two of which— Wall of Eyes and Cutouts— were released within an eight-month span in 2024.

Given the band’s power-trio format, it was perhaps inevitable that The Smile would be greeted with whispers that Yorke and Greenwood are “returning to rock,” a suggestion that’s loomed over every Radiohead project since Amnesiac’s glacial soundscapes melted into Hail to the Thief’s electric skronk. It’s a forecast that occasionally proves true: On the first Smile album, A Light for Attracting Attention, Yorke snarled and strummed through “You Will Never Work in Television Again” with a punk-ish aggression not heard from him since the 2007 Radiohead track “Bodysnatchers.”

But while The Smile is certainly guitar-friendly, their take on rock and roll is decidedly brainy, more about knotty arrangements than swing, soloing, or brunt force. On Cutouts highlight “The Slip,” guitars occasionally erupt with live-wire energy, matching the song’s jittery, herky-jerk funk. Wall of Eyes jam “Read the Room” doesn’t exactly riff, but it does use electric thrum to underscore the song’s sense of menace.

That’s a good indicator of where The Smile’s aesthetic interests lie— less in rocking with abandon, more in cultivating weird textures and provocative sound effects. Together, Wall of Eyes and Cutouts create the kind of sensuous, slightly unsettling dinner party ambiance that Christgau praised, in no small part thanks to the dramatic flourishes Greenwood has developed in his second career, writing music for film. String sections swell up at key moments— listen to the delicate filigrees that adorn “Instant Psalm,” or to the way “Tiptoe” recalls the kind of soured romance Greenwood conjured for Phantom Thread. Elsewhere, The Smile lean into the warm rustle of acoustic guitar strings (“Wall of Eyes”) and the gloopy burble of analog synths (“Foreign Spies”).

If these albums are about collecting different textures, they are equally committed to exploring wide-ranging rhythms— a commitment that aligns with Skinner’s rumbling jazz but also with the dance music Yorke became enamored with during Radiohead’s King of Limbs era. On Wall of Eyes, the title song begins the album with a gentle Calypso groove. Both albums feature several selections rooted in anxious funk— afrobeat as filtered through Talking Heads. The best example, and the highlight from either of the new albums, is “Zero Sum,” which finds Yorke singing about Windows 95 over woozy horns and agitated cowbell.

“Zero Sum” also happens to be one of the The Smile’s best guitar showcases. Writing for Stereogum, Chris Deville describes the song as “maybe the most frenetic track Yorke and Greenwood have ever given us,” specifically citing the “physical achievement” of Greenwood’s shredding— an intricate web of riffs, rendered with manic energy and mathematical precision. Several other songs, spread across the two albums, feature guitar motifs that are similarly dizzying and heady.

And then there’s “Bending Hectic,” the centerpiece of Wall of Eyes. It’s another Yorke lyric that fantasizes about crashing cars, and it culminates in the most euphoric rock guitar jam Greenwood and Yorke have offered since OK Computer— but only after a five-minute wind-up that doesn’t feel epic so much as tedious. As Deville writes, “The payoff is tremendous, but the journey there becomes a slog.”

It’s a slight stumble that illuminates some of the larger concerns keeping these albums from being unalloyed successes— tunes that aren’t quite as sticky as the ones on A Light for Attracting Attention, pacing that front-loads slower songs and causes the momentum to lag. What’s remarkable is how the group’s mastery of mood, and their rich command of textural and rhythmic idiosyncrasies, help to minimize these liabilities. For dinner party accompaniment that’s stimulating and evocative, you could do much worse.

All three albums by The Smile, ranked and rated:

A Light for Attracting Attention (7.5 out of 10)

Cutouts (7 out of 10)

Wall of Eyes (7 out of 10)

Coldplay - Moon Music

Delivering a speech in 2006, U2’s Bono offered this taxonomy: “Pop music often tells you everything is OK, while rock music tells you that it's not OK, but you can change it.”

It’s an appropriate sentiment for a man whose music, even as its most anodyne and corporate-glossed, has always feinted toward some type of social or spiritual agitation. It also goes to show that, for as much as Coldplay was once heralded as the heir apparent to U2’s arena rock throne, they’ve ultimately pursued a very different goal: If Bono’s vision of rock music is all about rousing and unsettling, Coldplay makes pop music through-and-through, alternating between consoling melancholy and feel-good anthems.

They’ve never felt quite so committed to succor as they do on Moon Music, their 10th and most frictionless album to date. Abandoning any lingering presentations of artsiness from their Brian Eno era, jettisoning the grim realism that occasionally penetrated the lyrics of Everyday Life, Moon Music is the aural equivalent of the “hang in there” kitten poster— a cute, vaguely heartwarming call to persevere, but one that consciously avoids meaningful acknowledgement of hardship or struggle.

The album title is just one letter away from reading Mood Music, and that’s fitting: Between its twinkling pianos, Day Glo synths, and cavernous sound, this is an album meant to conjure a celestial feeling, consistently chill and absent any earthbound grit. It’s a vibe that’s well-suited to the lyrics, which offer an invitation to pan out from everyday problems and instead see the bigger picture. The album’s premise might be summarized in this way: Life is hard, but the movement of the constellations suggests that even our hardships are part of a loftier, more beautiful orchestration.

This focus on heavenly bodies does not completely overshadow physical ones. Coldplay has now been delivering technicolor dance-pop longer than they ever did U2-style arena rock, and on Moon Music those instincts yield mixed results. “We Pray,” a multiculcutral stab at non-sectarian spirituality, is too portentous to be fun, but “feelslikeimfallinginlove”— produced by famed Robyn and Taylor Swift collaborator Max Martin— is one of their most appealingly featherweight concoctions since 2011’s Mylo Xyloto. On this song and throughout much of the album, the band’s saving grace is the state-of-the-art sound quality— simply put, Moon Music sounds luxurious and expensive.

As the group shifts away from guitar rock to dance-pop, the individual contributions of the band members feel less and less distinctive— save for singer Chris Martin, whose earnestness remains the group’s signature. It’s difficult even to discern the presence of a guitar until near the album’s end, when “All My Love” builds from acoustic strumming into a winsome stab at Beatles-esque psychedelic whimsy. You can also hear the rhythm section lock into the occasional appealing groove, as on the disco-lite “Good Feelings.”

Even these song titles reveal where Martin’s head is at— still full of dreams, swollen with good intentions. It’s increasingly difficult to remember the Parachutes and A Rush of Blood to the Head era, when Martin’s lyrics occupied a more anxious and agitated headspace; now he’s focused on positive vibes and empowerment anthems. In one song— appallingly titled with just a rainbow emoji— the voice of Maya Angelou floats through the ether, reminding us not to look at all the dark clouds in our lives, but to focus on the rainbow. Undoubtedly, the sentiment would hit harder if it was moored to the very real struggles in Angelou’s life, which are overlooked here in favor of a generic reminder that “storms pass, love lasts.”

Moon Music could almost serve as a hymnal for the “spiritual but not religious” crowd. “We Pray” is the closest the album comes to voicing real lament, yet it could be addressed to anyone or anything. The treacly “Jupiter” presents us with a heavenly billboard, its message bewilderingly anticlimactic: “Never give up, love who you love.”

It’s hard to be too upset about a band that seems motivated by positivity in an age defined by rancor— but what grates about Moon Music is how a group known for being emotionally articulate is caught sounding so tone deaf. In one song, ostensibly born of relational duress, Martin implores his partner to just remember all the “good feelings” they once shared while dancing to the radio. Coldplay is a band that conjures good feelings for many, but what they offer here feels like cold comfort indeed.

My rating: 5 out of 10.

Other recent favorites: