Billie's Blues

On her third album, Billie Eilish combines vintage song structures with a contemporary aesthetic. She also sings with more freedom and range than ever before.

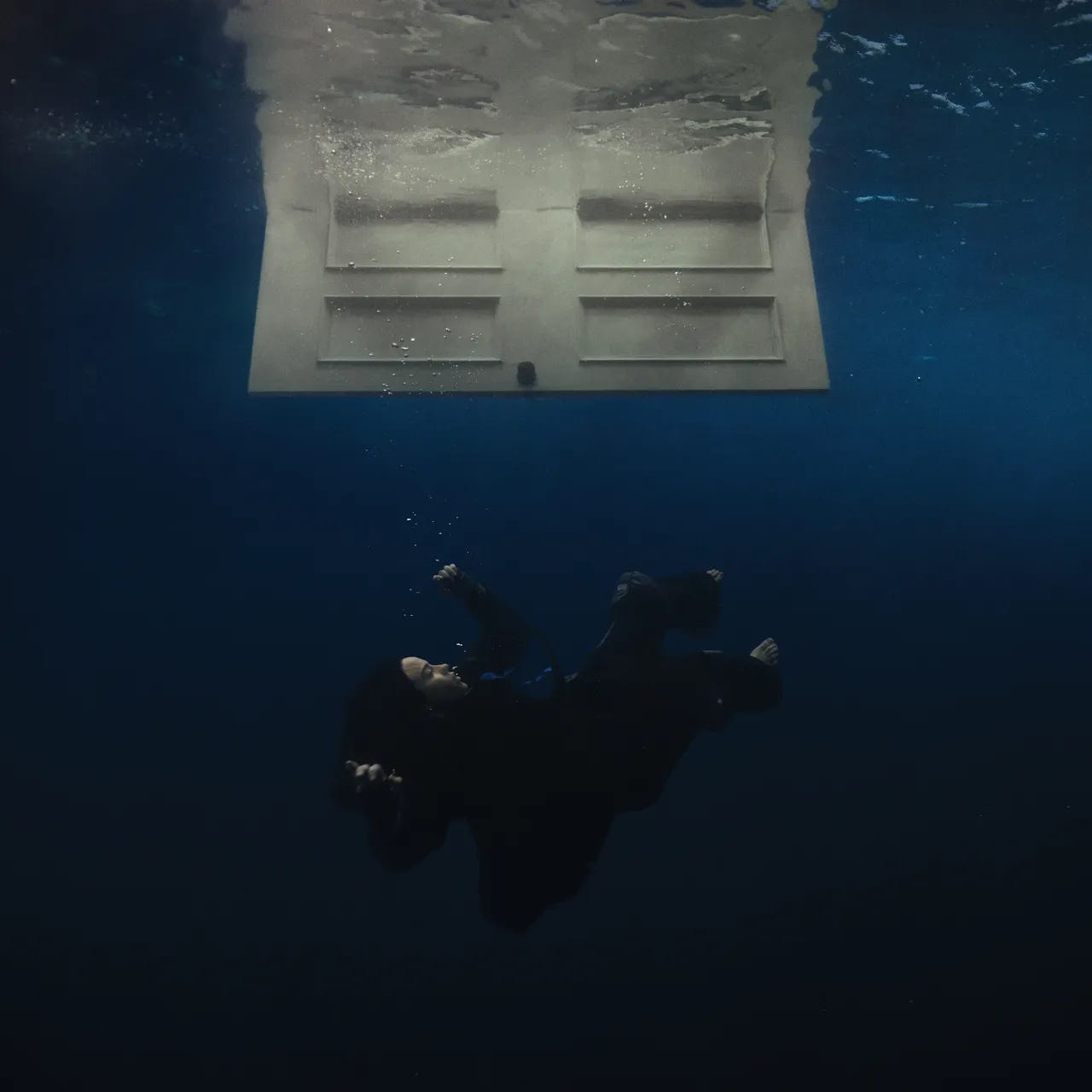

Billie Eilish - Hit Me Hard and Soft

Avid listeners to The New York Times Popcast will know that, any time 22-year-old singer Billie Eilish is invoked, a mention of the late, great Tony Bennett can’t be far behind. It may seem like an odd reference point, likening one of our poet laureates of youthful angst to Frank Sinatra’s favorite crooner, yet behind it there is an astute line of thinking— that for as much as she delights in contemporary sounds and modern vernaculars, Eilish is really a traditionalist at heart.

That much is evident not only from her albums but from her heavily decorated soundtrack work, including Oscar-winning themes from Barbie and No Time to Die. Co-written with her brother Finneas, these songs boast big, clean melodies and exacting structures— they have the bones, if not always the lyrics, of something that a showman like Bennett might have sung. Eilish voices these songs in a breathy style that feels confidential and conspiratorial— the instincts of a jazz singer, modulated for the earbuds era.

It’s possible to hear some of the same traditionalist instincts on Hit Me Hard and Soft, the third full-length team-up between Billie and Finneas. In an era of streaming opulence, where artists like Taylor and Beyonce can release sprawling works of unruly ambition, Hit Me Hard and Soft feels positively classicist with its lean 10-song run. It finds plenty of opportunity to showcase Billie the balladeer, and its reliance on feathery synths and Radiohead portent creates a coherent aesthetic palette.

Yet beneath this structuralist sensibility, Hit Me Hard and Soft reveals itself to be the most exploratory, form-breaking work Eilish has yet made. For one thing, more than half the songs here come with beat-switches, their semblance of traditionalism morphing into something more progressive. In “L’amour De Me Vie,” Eilish starts off swinging like a lounge singer— but just when it seems like the song is winding down, her intimate crooning gets Autotuned, and the song transforms into a rush of Tron-worthy synths.

There is nothing new about Eilish’s omnivorous approach to rhythms— not for nothing did her previous album include a highlight called “Billie Bossa Nova.” A large chunk of Hit Me Hard and Soft occupies a space best described as Space Age chill-out music— variations of lounge-y tangos and gently pulsing exotica. These rhythmic explorations provide the perfect marriage of Eilish’ twin impulses— her affection for traditional forms combined with a restless ear, born of the streaming age.

Every Eilish album need at least one truly sinister vibe— something with a weird beat and a malevolent tone, occupying the “Bad Guy” slot on the track list. Here, it’s “The Diner,” which feels pitched somewhere between a ballroom dance and Soundcloud demo. Amidst disorienting horror movie sound effects, Eilish whispers an unsettling story about a stalker— a prime example of her penchant for taking something that feels structurally airtight and dressing it up in an edgy, off-kilter aesthetic.

Even more representative of the album’s quietly exploratory nature is “Bittersuite,” a sadsack epic in three parts, condensed into a rangy five minutes. It opens with a whir of synths before settling into an eight-bit lounge number, a Calypso number rendered with chintzy sound effects and processed beats. Eilish has seldom sounded more comfortable than she does wrapping her whispery voice around the shape-shifting rhythms— until the concluding movement, a cinematic denouement of beeping synths and industrial noise.

And then there’s the album’s big single, “Lunch.” With its pile-up of brazen same-sex come-ons— “I want to eat that girl for lunch” barely qualifies as a double entendre, and “I just want to get you off” not at all— it’s positioned as something transgressive, at least attitudinally; certainly it’s the most explicitly lustful, sexually candid song Eilish has ever recorded. And yet, in terms of its form, it’s the most straightfowardly pop thing here, a celebration of sneaky hooks that could almost pass for a 4*Town crowd-pleaser. The song is so punchy, it makes some of the subsequent ballads feel drowsy by comparison.

“Lunch” isn’t the only pop confection here. The lovelorn “Birds of a Feather” could almost pass for an R&B tune, and features some of Eilish’s freest singing. Though the lyrics gesture toward an ongoing morbidity— “I’ll love you til the day that I die” sounds like she means it quite literally— Eilish herself sounds unencumbered; happier than ever, to coin a phrase.

It’s one of a few songs here where she does new things with her voice, not forsaking her gifts as an after-hours crooner but demonstrating that she’s capable of so much more. “The Greatest” starts off quiet and wispy, but builds into a huge arena pop conclusion. Eilish meets the song’s raw emotion with her biggest and best Adele-style belting yet.

The freedom in her singing is often in tension with the lyrics, which fumble for love and connection amidst forces outside the singer’s control. Melancholy opener “Skinny” wrestles with body image, public perception, and the savagery of Internet culture, casting Eilish’ success as a bad dream from which she can’t wake up. It’s the one song here to continue the tortuous ruminations on fame that characterized Happier Than Ever, keeping her in direct conversation with Olivia and Taylor— two other women who have had to navigate the transition to adulthood fully in the public eye.

Loss of control is a recurring motif throughout the album. “Things fall apart and time breaks your heart,” Eilish sighs in “Wildflower,” an aching acoustic ballad. In “Birds of a Feather,” she can’t help but consider new love in light of the grave, imagining the relationship ending not just with tears, but an actual casket. Even “Lunch,” far and away the giddiest song here, finds the singer abandoning herself to instinct and appetite: “It’s a craving, not a crush.” Tellingly, one song takes its name from “Chihiro,” the little girl at the center of Hayao Miyazaki’s film Spirited Away, who’s forced to grow up fast after being lost in a dark wonderland.

Hit Me Hard and Soft may not quite qualify as a coming-of-age story the way Spirited Away does, yet it does wind its way toward a moment of personal revelation. The album concludes with “Blue”— another multi-part suite, another classicist gesture— which finds Eilish acknowledging her own limitations in a troubled relationship: “I don’t blame you/ But I can’t change you/ Don’t hate you/ But we can’t save you.” It’s an assured conclusion to an album that finds Eilish sounding, more than ever, confident in her own voice.

My rating: 7.5 out of 10