Chronological Conundrums

Dynamic new albums from Ethan Iverson and Sullivan Fortner make jazz antiquities sound fresh and modern.

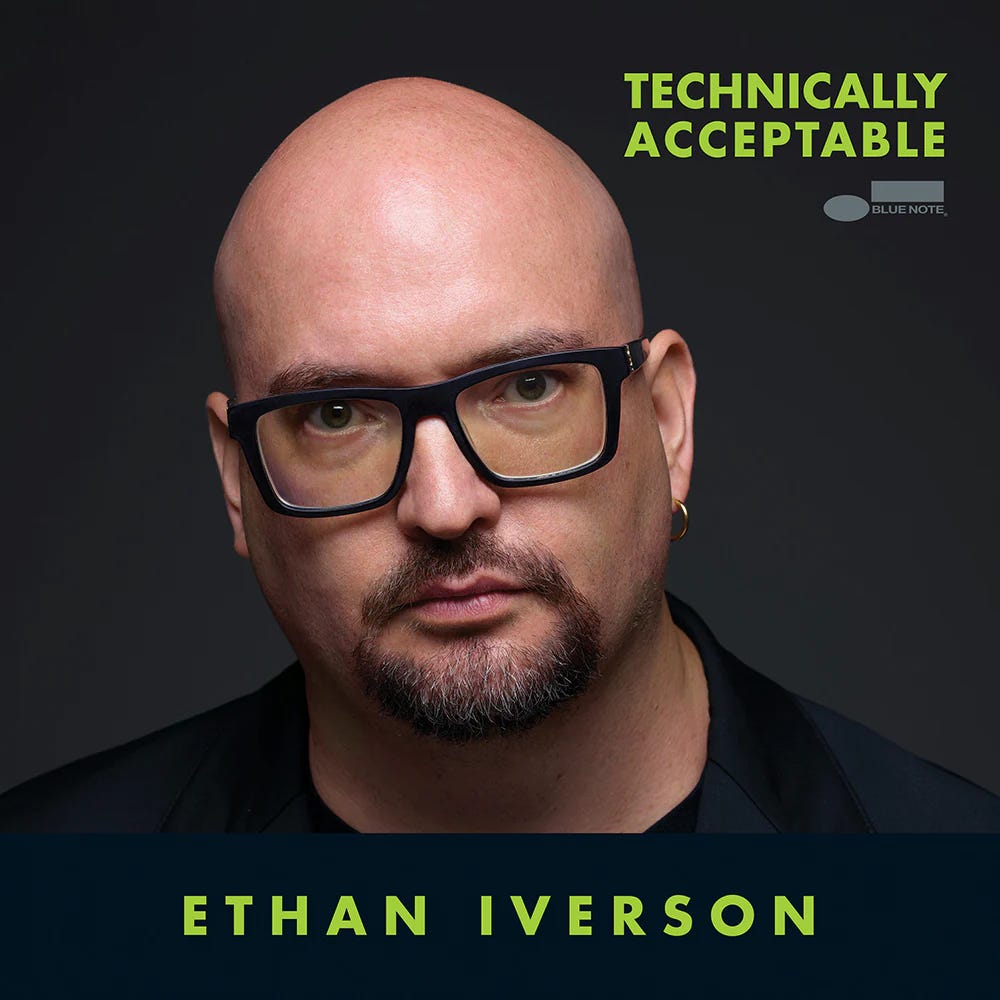

Ethan Iverson - Technically Acceptable

Ethan Iverson opens his new album with “Conundrum,” the ebullient opening theme music from the TV game show of the same name. If you’ve never seen the show, that’s because it doesn’t actually exist. It’s merely a conceptual flight of fancy— an excuse for Iverson to open his album with 90 seconds of glittery piano jazz confetti.

It’s hard to think of a more fitting introduction to Iverson’s musical persona— wry, brainy, conversant with pop culture, given to geeky obsession with niche interests. In his must-read newsletter Transitional Technology, the pianist writes prolifically about jazz past and present, but also about 70s car movies, the crime fiction of Donald Westlake and Charles Willeford. He brings that same kind of nerdy enthusiasm to Technically Acceptable, his second solo release on the venerated Blue Note label.

Iverson has been a purveyor of historically rooted, intellectually robust, and broadly accessible jazz music for decades now. As one third of The Bad Plus, he wrangled tunes by Nirvana and Blondie into the jazz canon, fitting them alongside feature-length reimaginings of Stravinsky and Ornette Coleman. Iverson left the group in 2017; The Bad Plus has soldiered on with albums that sound, to my ears, fairly workmanlike. The spunk and spirit of the band’s classic era now live on in Iverson’s solo recordings.

Technically Acceptable is the finest of those recordings to date, and one of the three or four best albums Iverson’s ever been involved with. It’s an arresting tribute to the pianist’s lifelong endeavor to recast traditional jazz tropes with a fresh, contemporary attitude. Not for nothing does Mike Jurkovic liken the album to a funhouse; the record includes 13 songs, and at least as many trick-mirror images of tried-and-true piano jazz conventions.

In the past, Iverson has generally recruited elder statesmen to support his solo compositions, living legends like Ron Carter and Jack DeJohnette. For Technically Acceptable, he opted for a cadre of younger players, recording the bulk of the album with bassist Thomas Morgan and drummer Kush Abadey. Their youthful energy is a perfect complement to Iverson’s rush of ideas: Where previous album Every Note is True lingered long for elastic improvisation, most of the new songs fly by in two to four minutes’ time, as if the band is eager to cover as much ground as possible before the momentum flags.

The first seven songs, cut with the Morgan-Abadey band, unfold with the tunefulness and energy of a pop record, all while demonstrating Iverson’s studious affection for the forms and idioms of the 20s and 30s. After “Conundrum” opens the album like uncorked champagne, “Victory is Assured” presents a hip, modernist update on Basie-style blues. The cool-struttin’ title song features cosmopolitan minimalism from Iverson, and a rhythm section that veers closer and closer to anarchy. Several songs bring big Dave Brubeck energy, sounding intellectual but also readily accessible.

The album’s middle section jettisons the Morgan-Abadey lineup, and demonstrates further evidence of Iverson’s progressive-traditional approach. A tender version of “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” recorded with bassist Simón Willson and drummer Vinnie Sperrazza, highlights Iverson’s porous, borderless approach to the standard— in this case an R&B standard.

Most striking of all is the Thelonious Monk chestnut “Round Midnight,” presented as a surreal duet between Iverson and theramin player Rob Schwimmer. It’s hardly the first time this composition has appeared on a Blue Note release, but it is the first time it’s been rendered quite so playfully.

In another Blue Note first, Iverson closes the album with a 15-minute piano sonata, drawing from pre-jazz American influences as wide-ranging as Aaron Copland and James P. Johnson. It’s an accomplished piece of music, highlighting still more aspects of Iverson’s personality— Iverson the piano teacher, the classical music scholar, the technical virtuoso. To my ears, it’s less giddy-fun than the rush of inspiration that precedes it, though it’s still a perfectly fitting denouement for an album so jam-packed with ideas.

On Technically Acceptable, Iverson fortifies his position as one of the standard-bearers of jazz, steeped in its history but not stuck in it. These new songs present that history as an open invitation to curious listeners everywhere.

My rating: 8 out of 10

Sullivan Fortner - Solo Game

It never fails. No sooner do I make my year-end albums list than I belatedly discover an album that should have been on it. Consider this a mea culpa for overlooking Solo Game, an arresting solo piano record from up and comer Sullivan Fortner.

To be fair, Fortner’s music wasn’t completely absent from my list. You’ll hear him behind the keys on Mélusine, the bewitching album from singer Cécile McLorin Salvant, with whom Fortner is a long-time collaborator. Meanwhile, several of our most discerning jazz critics did include Solo Game among their top recordings of the year, including indispensable experts Fred Kaplan and Nate Chinen.

Both critics rightly adduce Solo Game as an ambitious entry in the long tradition of solo jazz piano recitals; like Ethan Iverson, Fortner conveys both a reverence for jazz lineage and a bent toward making music that’s novel and progressive. Solo Game is neatly bifurcated into two halves, each one evincing that ambition in a different way.

Had Fortner released the first nine songs alone, the project would have been received as a model recital, exhibiting a wide repertoire, technical virtuosity, and a broad emotional spectrum. Surely some of the credit is due to producer Fred Hersch, who has released plenty of engaging solo piano music under his own name. (In addition to Hersch, Fortner has been mentored by Jason Moran, whose Modernistic remains my favorite solo piano record of the past 25 years.)

Fortner’s playing demonstrates a wide-ranging vocabulary of influences, without ever feeling too showy. He plinks his way through an opening rendition of Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry About a Thing” with a whimsical minimalism straight out of Solo Monk, while other songs revel in florid runs that remind me of Oscar Peterson. The album’s first act concludes with a tender, lyrical reading of Duke Ellington’s “Come Sunday,” pitched midway between a daydream and a prayer.

Then comes a 15-second interstitial track called “Power Up,” recalling vintage video game fanfare. It signals the shift into the album’s bold, electrifying second half, which finds Fortner dressing up his solo compositions in layer upon layer of one-man-band effects— prepared pianos and keyboards, drum loops, wordless vocals.

As carefully decorated as the set of a Wes Anderson movie, this adventurous second act sacrifices a little bit of the improvisational freedom and pure showmanship of the album’s first half. But what it lacks in instrumental finesse it makes up for in its rich assortment of textures and mood-altering sonic details. If the first half of Solo Game is a testament to Fortner the player, the back half bears witness to his brilliance as a composer and conceptual thinker.

Again, there are a number of reference points. Fortner’s immaculate miniatures point back to Mwandashi-era Herbie Hancock, or to MAST’s imaginative Thelonious Sphere Monk project. The old-timey vibe of “Stag” places it in the same lineage as Moran’s classic period piece “Moran Tonk Circa 1936.”

The album concludes with a pair of voice commentary tracks— the first from Hersch, the second from Moran— each explaining exactly why they find Fortner such an apt pupil. Their comments are impossible to disagree with, yet they also feel superfluous: In heralding the brilliance of Sullivan Fortner, Solo Game speaks for itself.

My rating: 7.5 out of 10