"Look what I'm digging up!"

Long-tenured rock and rollers Sleater-Kinney and Green Day return with new albums-- and both sound like they have something to prove.

Sleater-Kinney - Little Rope

Sometimes death announces itself with a premonition. When Nick Cave released his chilling 2016 album Skeleton Tree, it featured unnerving lyrics about the tragic loss of his son Arthur— though the singer insisted he’d written those words before Arthur’s sudden demise. Similarly, an outstanding new Sleater-Kinney album, Little Rope, was written before a car accident claimed Carrie Brownstein’s mother— yet the new songs seem to anticipate her loss.

Then again, you might say that a pallor of loss has been hanging over Brownstein and her long-time musical partner, Corin Tucker, for several years now. Little Rope is only the second album they’ve released since the abrupt exit of drummer Janet Weiss, whose muscular playing seemed an essential part of Sleater-Kinney’s alchemy. The first album they made without her, Path of Wellness, felt directionless, suggesting that the band’s streak of inspired record-making had finally come to an end.

Whether galvanized by grief or by the simple recognition that they have something to prove, the duo version of Sleater-Kinney sounds revitalized on Little Rope. Though the mood is unrelentingly solemn, the songs are streamlined and purposeful. Blazing through 10 tracks in just over half an hour, Brownstein and Tucker seem fresh and energized.

That’s not to suggest that the album aims for the same classic rock grandeur of The Woods, nor the same breathless punk frenzy of Dig Me Out. Sleater-Kinney already covered that ground with Weiss, and her departure frees Brownstein and Tucker to explore new moods, grooves, and textures— to break away from the expectations of their imperial era.

Little Rope does dabble in punk-rock intensity, if not punk-rock speed. Opening song “Hell” begins with chilly minimalism, erupting into cathartic squalls during the chorus. It sets the tone for the album’s hard, lean sound, dominated by noisy synths, distorted bass, and minimalist Brownstein guitar lines that occasionally burst into cacophony.

Crucially, the album finds Sleater-Kinney regaining their footing without jettisoning the lessons they learned in the wilderness. Little Rope is a rock album through and through, but it retains some of the textural experiments of The Center Won’t Hold and Path of Wellness. It’s also their most groove-centered record yet, thanks in no small part to the participation of touring drummer Angie Boylan. Late-album highlight “Crusader” rides to a steady disco pulse, while “Hunt You Down” wraps gnarled guitar riffs around a throbbing new wave beat. Decked out with synths and drum loops, “Say it Like You Mean It” may be the band’s best pure pop song.

Given the tragic circumstances that inform the album’s presentation, it’s tempting to think of it as a Brownstein-centered record— yet one of the most affecting touches on Little Rope is how Tucker rises to meet her bandmate’s pain, taking lead on most of the songs and delivering mesmerizing performances throughout. Compare her singing in the cathartic closer “Untidy Creature” to her unsteady warble from the Dig My Mood era and it becomes clear how refined she’s gotten, gaining control without sacrificing any of her power. This is her best work since The Woods.

The lyrics give voice to various stages of grief and vulnerability, often spiked with tart humor. In “Small Finds,” Tucker likens herself to an anguished dog, digging, scratching, or gnawing her way to some tiny moment of relief. “Don’t Feel Right” runs through a laundry list of self-care efforts: “Read more poems, ditch half my meds/ Dress my age, call back my friends.” “Untidy Creature” distills the album’s weary spirit into a hopeful question: “Could you love me if I was broken?”

These songs taxonomize bereavement in different forms. “Say it Like You Mean It” is a breakup song, and a spiritual sequel to the band’s classic “One More Hour.” Meanwhile, “Crusader” surveys societal decay— and the gun-toting white men who feel called to be messiahs. Yet Little Rope never collapses under the weight of its grief. On the contrary: Backed into a corner, Sleater-Kinney have regained their fighting form.

My rating: 8 out of 10

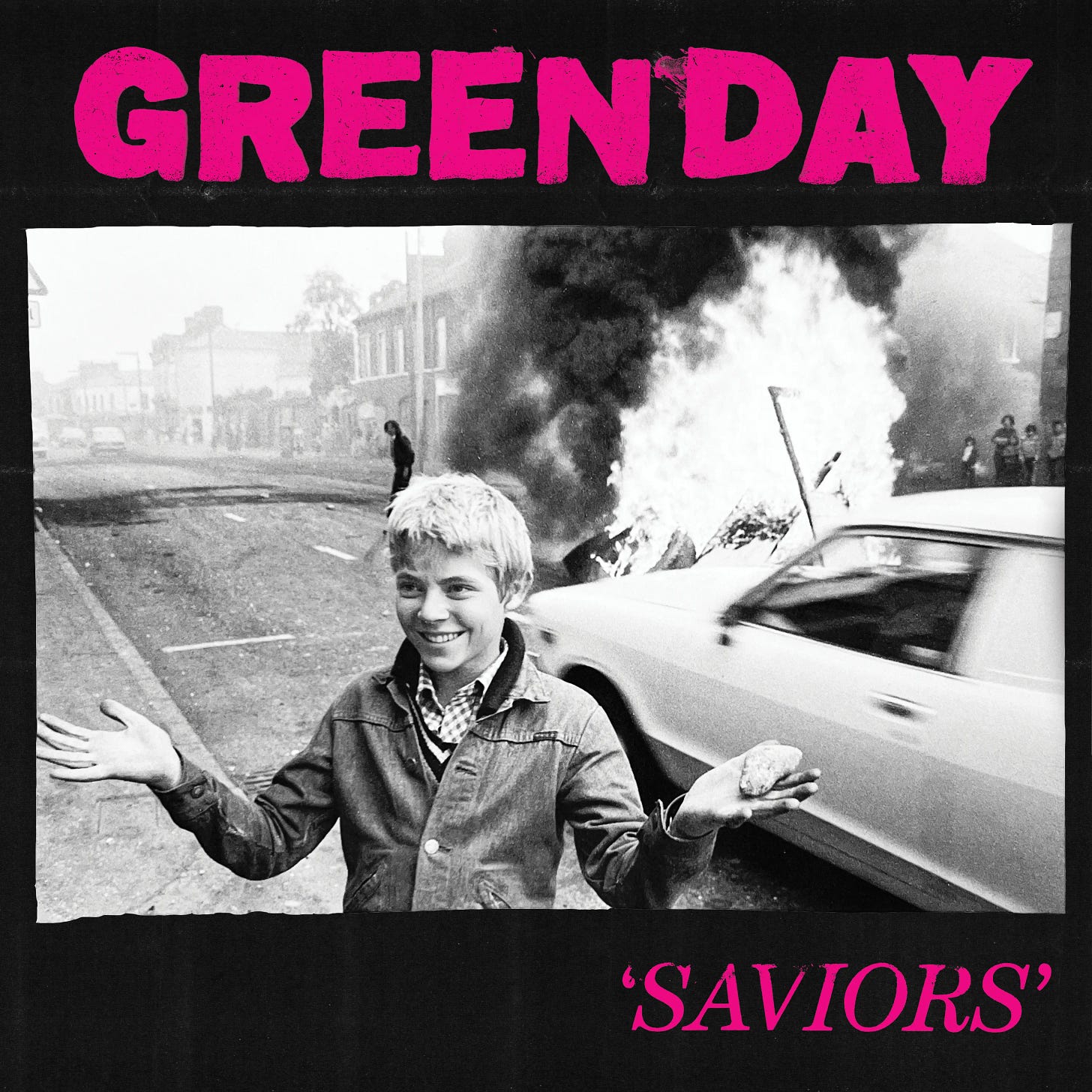

Green Day - Saviors

It’s difficult to think of a band more burdened by its own sense of importance. Green Day cut their teeth on loud, spunky pop-punk tunes that reveled in adolescence. Then, in 2003, they channeled anti-Bush sentiment into an era-defining album called American Idiot, a full-fledged rock opera that was eventually adapted for Broadway. Since then, every Green Day album has either tried to one-up American Idiot, or to pretend like it never happened.

At least that was the case before Saviors. Like many albums from middle-aged rock and rollers, Green Day’s latest attempts to synthesize disparate strands of their earlier work, not breaking new ground so much as consolidating core strengths. It’s billed as a deliberate return to the loud, snappy tunes of the band’s early years, laced with curdled political angst and a few lingering arena rock flourishes.

The band cut Saviors with Rob Cavallo, the producer who helmed basically all of their classic-era records, and they’ve used every opportunity in their press cycle to position the album alongside Dookie and American Idiot. Not since U2 made How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb has a venerable rock band worked so hard to convince listeners that they’ve emerged from the wilderness with an album that stands alongside their classics. There are enough winsome moments on Saviors to affirm Green Day’s basic strategy, yet it’s the album’s innate conservatism that prevents it from being the revitalization they clearly want it to be.

When the album works, it’s a reminder of how satisfying Green Day can be when they’re in pure pop-punk mode, bashing out quick and simple songs with brash, bratty energy. A sequence of hard-charging songs at the album’s center— “Coma City,” “1981,” “Suzie Chapstick”— are especially pleasing, functioning as reminders of how far this band can run on melody and slapdash energy alone. Just as good are the songs fortified by the sing-along spirit of early rock and roll, as on the cowbell-heavy bash “Corvette Summer.”

These songs provide persuasive evidence of Green Day’s iconic stature, and make it easy to believe that their classic albums might remain a lodestar for a new generation of performers. As Amanda Petrusich writes in The New Yorker, there is a sense in which the zeitgeist has caught up with Green Day, as their influence saturates recent records by Olivia Rodrigo and Billie Eilish.

Perhaps that’s what makes it so frustrating to hear Green Day sound so insecure about their reputation. Along with Cavallo, they take out a number of insurance policies to make certain their hard-and-fast approach hits home, not only by cranking up the volume to deafening extremes but also by overdubbing guitars with keyboards and string sections. In other words, this is a long way from the ragged sound of Foxobro Hot Tubs, the band’s garage rock alter egos. Here they’re playing not with abandon but with calculation, carefully ensuring all the right signifiers are in place to recall the glory days of Dookie.

That sense of calculation undercuts the effect of Billie Joe Armstrong’s lyrics, especially the songs that feel intended to provoke. “Bobby Sox” is ostensibly a transgressive song about sexual and gender fluidity, but it lands more like a safe bet on what the ideological marketplace can handle in 2024, a song that bears a provocative posture but doesn’t say anything terribly counter-cultural.

Elsewhere, Armstrong’s gift for channeling anti-rightwing rage fails him. You would think it would be an easy task in an election year that finds the Republican party once again coalescing around Donald Trump— a convicted sexual abuser, failed insurrectionist, and noted Nazi sympathizer. Yet somehow the best Armstrong can offer is libertarian madlibs: “Don’t want no huddled masses/ TikTok and taxes/ Under the overpass/ Sleeping in broken glass.”

The cranky old man schtick is ill-suited for an album explicitly aimed to remind us of Green Day when they were younger. It results in an album that frequently entertains, but fails to clarify the way forward for this august band. By trying to recapture their youth, they draw considerable attention to their middle-aged malaise.

My rating: 5.5 out of 10

Sprints - Letter to Self

If Sleater-Kinney and Green Day provide different models for rock bands to navigate middle age, Sprints offers a compelling coming-of-age story. On their debut album, a cathartic blast called Letter to Self, the Dublin four-piece captures the intense, pent-up anguish of being young. For a more tortured chronicle of what it feels like to be on the back end of teenage angst, you’d have to go back to— well, last year’s Olivia Rodrigo album.

Almost without exception, the songs on Letter to Self channel inner turmoil through slow builds and explosive climaxes— their songs simmer in rage before erupting into thunderous, U2-style euphoria. The slow-burning menace of early PJ Harvey is another touchstone. Producer Daniel Fox, a veteran of Ireland’s punk scene, captures their stark dynamics in noir-ish black-and-white, only occasionally pushing Sprints to vary their sonic and emotional palette: “A Wreck (A Mess)” is wry and dancefloor-ready, while “Literary Mind” captures the rush of new romance.

These songs are exceptions to the rule, and most of Letter to Self is harrowing both in sound and in subject matter. Powerhouse singer Karla Chubb characterizes the album as an outpouring of righteous anger, and she has much to be angry about. “Cathedral” unpacks the sexual repression of an Irish Catholic childhood, while “Can’t Get Enough of It” considers the traumatic after-effects of abuse: “I still shiver every time I hear the door shut/ I still quiver every time you hear my name.”

On the latter song, Chubb’s pain feels like a prison— but if the album proves anything, it’s that pain can be rocket fuel for shared uplift and escape. The title song closes the album by bending Chubb’s anguish into iron resolve: “Any habit can be broken/ Any night can become day.” Even better is “Up and Comer,” a chest-thumping tale of underdog triumph: “And if you beat her like a drum… I bet she’ll fire for you still/ I swear to god she’ll make a start.”

On Letter to Self, Sprints makes more than a good start. They solidify themselves as a new band worth getting excited about.

My rating: 7 out of 10