My 10 Favorite Albums

At The Hurst Review, answering the age-old "desert island" question is an annual tradition. Here's this year's ballot.

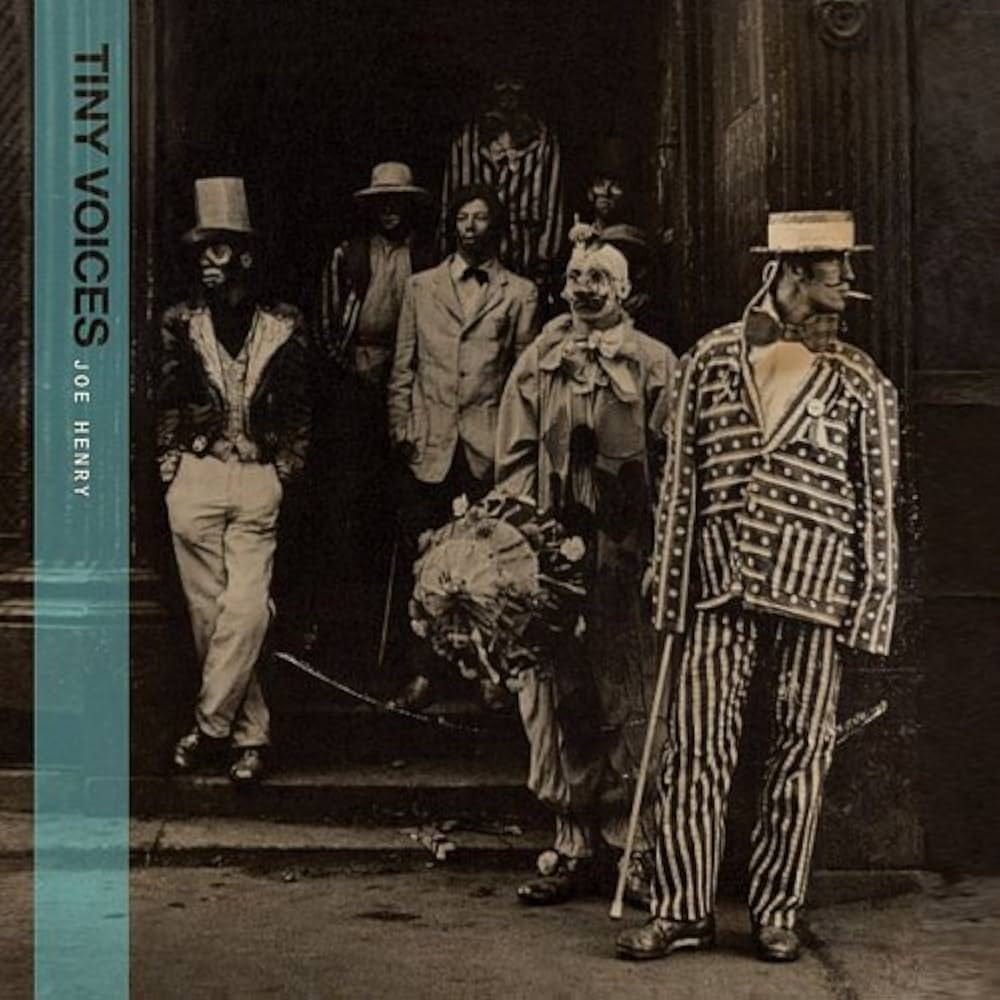

1) Joe Henry - Tiny Voices

One of Joe Henry’s great gifts is writing melodies with a distinctly 20th century romance— many of his songs feel like standards, with tunes that might sound natural emanating from the Duke Ellington Orchestra, or perhaps a crooner like Tony Bennett. Tiny Voices, his landmark album from 2003, may be the peak of his melodicism; every tune sounds like a tattered page from the Great American Songbook, an excavated record from a half-remembered, half-imagined past.

But no midcentury song-and-dance man would play these songs in quite this way. To make Tiny Voices, Henry convened a ragged troupe of jazz and rock session players in an old Hollywood movie studio, presented them with bare outlines of his songs, then let them go wild. So while the album is tuneful it’s the furthest thing from mannered— its tight formalism provides the scaffolding for scruffy performances, an improvisational spirit, a palpable sense of discovery.

The songs were all written in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and America’s subsequent descent into vengeful thinking and blood lust— though the album’s not really interested in politics or war. It’s interested in the human preference for fiction over truth; the inevitability of our self-deception. Henry’s narrators are world-weary, wise, often jaded— but just as often, startlingly romantic.

Perhaps that’s because the world of human intention is cast here as just one realm within a much wider universe— on one song, Henry acknowledges the looming specter of “bigger things unseen.” God shows up in the title song to recount the grisly lead-up to the Exodus, promising a righteous love that’s not for the faint of heart— a love that breaks down our delusions and promises something better than the paltry tidings for which we so often settle.

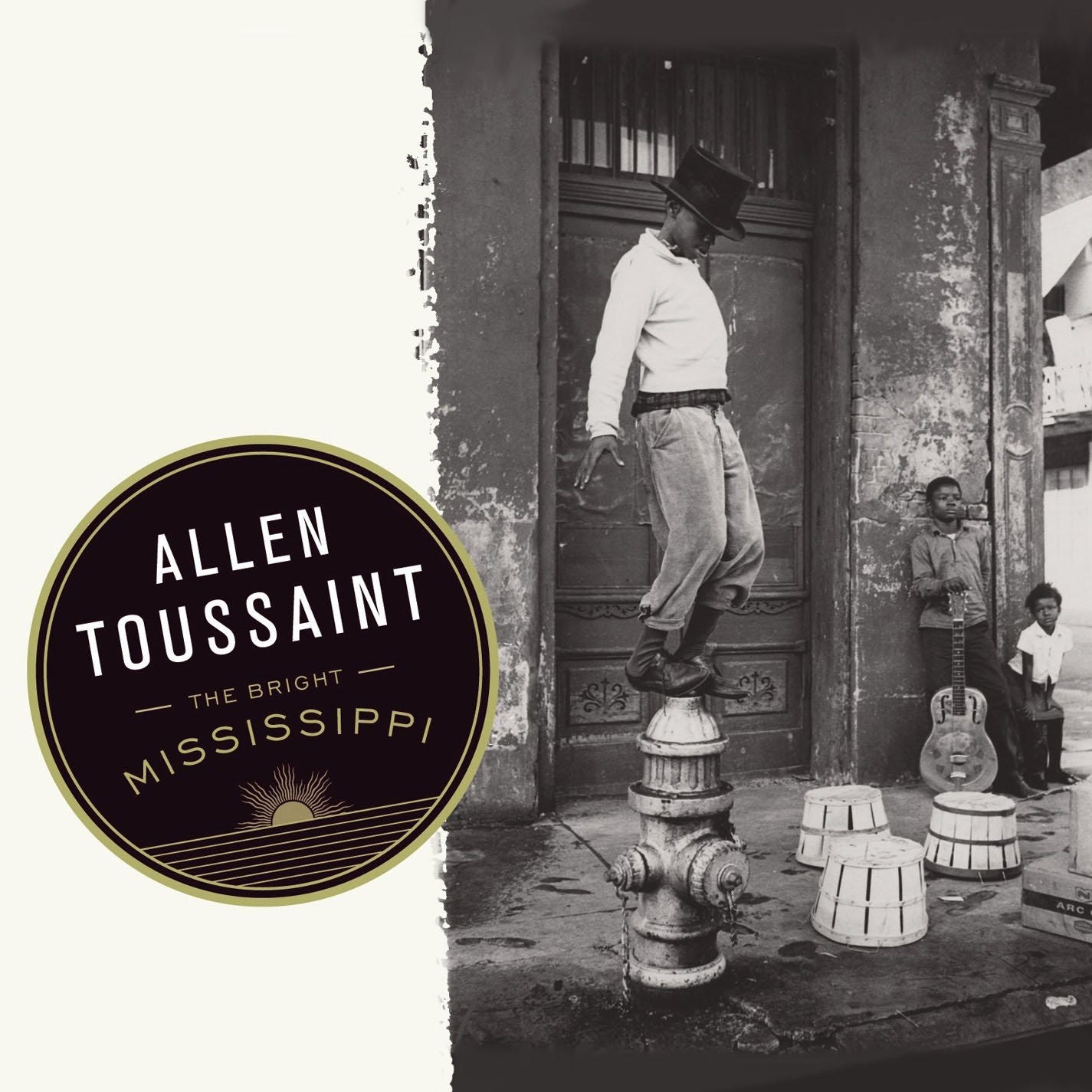

2) Allen Toussaint - The Bright Mississippi

Before he made The Bright Mississippi, Allen Toussaint was known primarily as the ever-dapper first gentlemen of New Orleans— a behind-the-scenes player whose songwriting and production credits shaped generations of soul, R&B, and funk. Scholars and cratediggers may know his name from the work he did with The Meters and Lee Dorsey; Little Feat and Bonnie Raitt.

With the mostly-instrumental The Bright Mississippi, Toussaint proved himself to be a supreme interpreter of his city’s musical legacy— a tour guide who can point out local landmarks but also imbue them with personal narrative and evocative lore. The songs here are all about New Orleans, written by native sons, or simply associated with the city’s singular spirit in some way— think classics by Armstrong and Monk, Duke Ellington and Sidney Bechet.

This is Toussaint’s great piano record, and while he’s a skilled player with a wonderfully smooth, elegant style, The Bright Mississippi isn’t foremost about virtuosity— it’s about communal joy and uplift. Leading a small combo of elite players, Toussaint carries these melodies with infectious enthusiasm and joie de vivre.

Standards records can feel rote, but the magic of The Bright Mississippi is how it never sounds like a museum exhibit or a dusty old historic excavation— it moves along to the rhythm of a parade; it’s not an academic affair, it’s a straight-up dance party. And while the songs all hail from the jazz tradition, it really feels more like folk music— melodies that have been received through the oral tradition and are preserved but not suffocated by these endlessly cheerful, idiosyncratic performances.

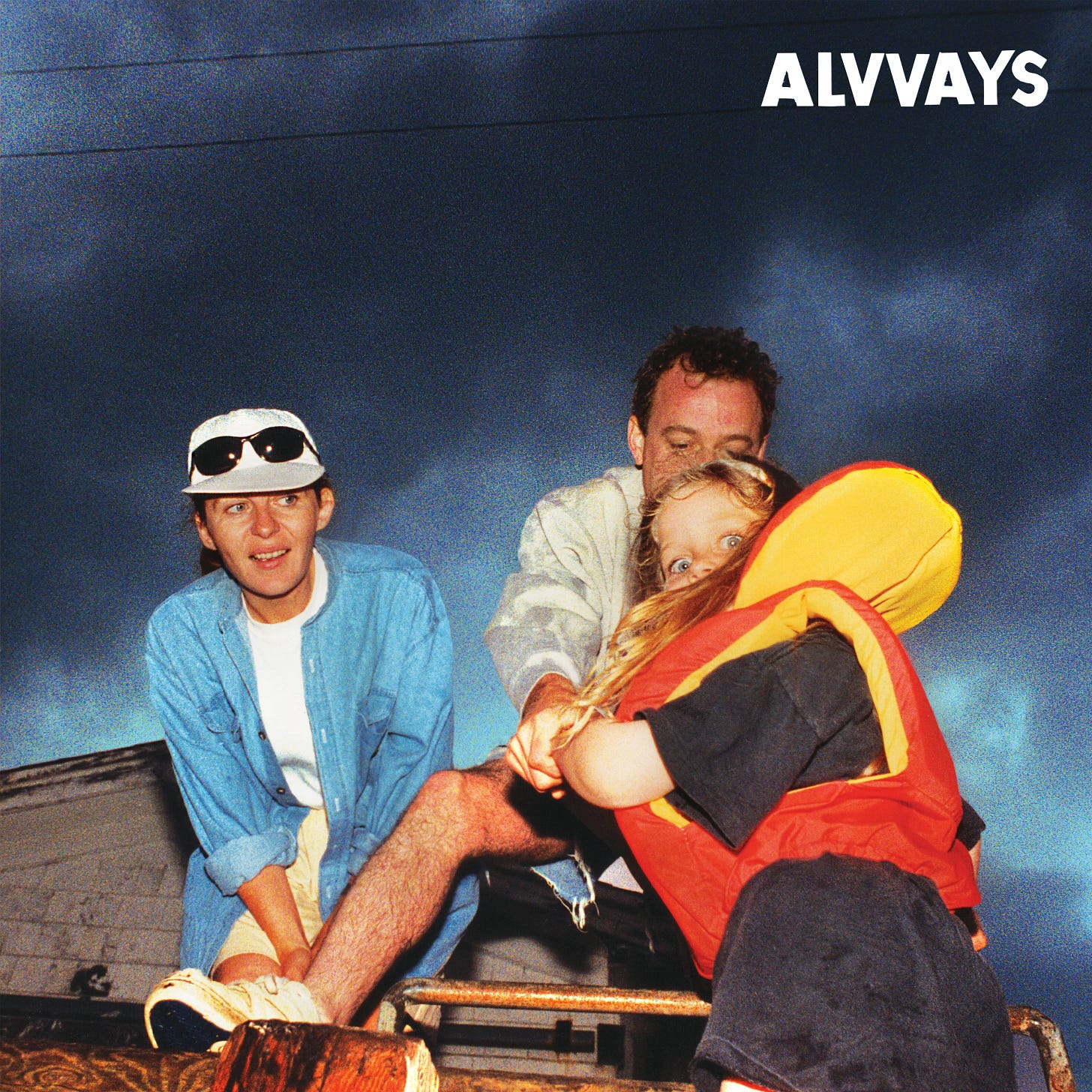

3) Alvvays - Blue Rev

In less than 40 minutes’ time, Blue Rev provides a condensed history of college and underground rock, its songs containing endless power pop taxonomies— from shoegaze to synth-pop and beyond. “After the Earthquake” scratches the itch for that early R.E.M. jangle; “Pressed” is a perfect homage to The Smiths; and what is one to make of a song named for Television frontman Tom Verlaine? To the extent that the album is a reflection of its auteur’s record collection, Blue Rev confirms the member of Alvvays to be vast in their knowledge, hip in their sensibilities.

But the album is not just a demonstration of good taste— it’s also a masterpiece of craft and emotion, two qualities that are directly related to one another. The’s an embarrassment of hooks here, arriving in an endless cascade, and the songs are perfectly sequenced to make each tune feel somehow bigger and grander than the one that came before it. The clean lines of the verse-chorus-bridge songwriting provide the perfect framework for the album’s vivid feelings— namely, all the panic and second-guessing, all the moments of joy and seasons of malaise that come with young adulthood.

It also sounds great. Alvvays is a band that courts bright colors, channeling their tunes through oceanic guitar effects and featherweight synth effects— but if Blue Rev is very much a triumph of studio craft, it also captures a great band playing with confidence and vigor. The group performed these songs one-after-the-other in the studio, and the performances capture the ragged momentum— the exhilaration and the creeping exhaustion— of a live set.

The lyrics, all written by singer Molly Rankin, capture young people at inflection points— on the cusp of either blowing up or doubling down on a relationship— and they convey all the dread uncertainty that comes from making big decisions with real stakes. Rankin’s songs contain the pungent humor and crunchy details that make English majors swoon— my favorite is when she rhymes “stretcher” and “Jessica Fletcher”— but her writing is as much about emotion as intellect. And the characters she inhabits— smart but introverted women whose biggest obstacle is their own self-doubt— are endlessly lovable, even though they seldom seem to know it.

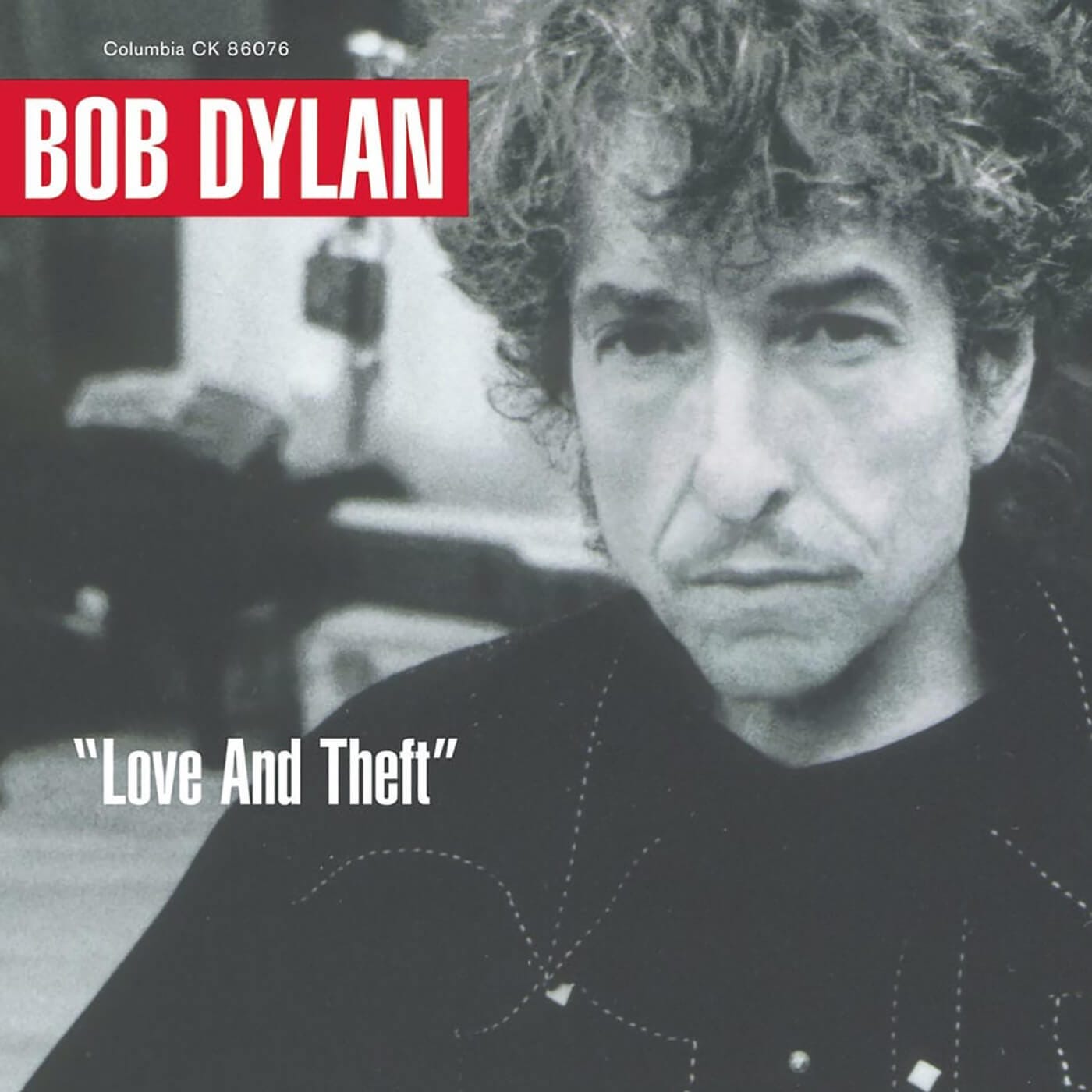

4) Bob Dylan - Love & Theft

There are albums, even entire eras where it sounds like Bob Dylan’s heart just isn’t in it— but nobody would ever say that about Love & Theft, the astonishing latter-day masterpiece that finds him cackling, snarling, cracking jokes, and acting like he’s having the time of his life. He borrows an old Groucho Marx routine; he makes puns; he shares a few ribald pickup lines, and he even makes a knock-knock joke. Both in terms of joke density and joke quality, this is the funniest Dylan album— and the one where it sounds like he’s having the most fun.

Following the muted, holy-moment glow of Time Out of Mind— a masterpiece of a different sort— Love & Theft feels visceral in its command of wide-ranging American roots idioms, from grinding blues to rollicking swing to old-timey soft-shoe crooning. It’s also the perfect encapsulation of Dylan’s own long and rambling journey— consider it a cross-pollination of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan’s love of folklore, the garage rock energy of his electric recordings from the 60s, the tall tales and mythmaking of The Basement Tapes, even some of the gospel undercurrents of his Born Again era.

The songs are endlessly complicated. They’re full of jaded characters who all seem to inhabit a semi-fictional pre-War America— they dabble in Vaudeville, they swap Civil War stories, they dance to old Robert Johnson tunes, they take a skeptical view of Charles Darwin’s crank theories. But the world of Love & Theft is hardly confined to the dustbins of history— how unnerving was it when this album, released on September 11, 2001, invoked a “sky full of fire, pain pouring down?” Is there nothing new under the sun?

For as hilarious as this album can be, it also suggests that Dylan’s Christian conversion was no laughing matter. His writing here is deeply suspicious of mankind’s capacity for self-improvement— amidst the social, economic, and ecological calamity of “High Water,” nobody can save themselves from drowning, let alone one another. But in “Summer Days,” Dylan swears he knows “a place where there’s still something going on”— his heart still in the Highlands— and in “Sugar Baby” he ends with an exhortation for us all: “Look up, look up, seek your Maker/ ‘fore Gabriel blows his horn.”

5) The Innocence Mission - Birds of My Neighborhood

It’s hard to think of a songwriter whose lyrics work better as standalone poetry than those of Karen Peris, lead singer for The Innocence Mission. Her songs can all be arranged on the page in tidy, immaculate stanzas— mannered writing that channels deep rivers of emotion.

The clean lines of her writing are complemented by the band’s quietly transfixing sound— Karen’s voice pure and high, husband Don’s guitar ringing out as clear as a church bell. The spare, gentle sound of this band is like a balm, an oasis from the hustle and bustle of the outside world— and they perfected it on Birds of My Neighborhood, their intimate treasury of devotional poetry and tranquil folk music.

But while these songs have a placid exterior, the interior is roiled by deep sorrow. This is an album born from an anguished season in a couple’s life, with a few telltale lyrics— references to being birdless, flowerless— hinting at struggles with miscarriage or infertility. One song features a prayer from Karen— “If I could, I’d no longer be barren”— that ranks among the most haunting line readings of all time.

Yet Birds of My Neighborhood is not just an album about enduring a difficult season— it’s about clinging to faith and maintaining a joyful countenance, even when all the tidings seem grim. A song called “July” offers this stark admission: “The world at night has seen the greatest light/ too much light to deny.” Perhaps it’s a song about summer, but it feels more like Advent— the dawn of hope. This isn’t just a great album; it’s a life preserver.

6) Miranda Lambert - The Weight of These Wings

Country music has a rich lineage of storytelling, and often those stories center on heartache and divorce. The Weight of These Wings is not just a high watermark for long-form country storytelling— its 90 minutes unfolding with the depth and complexity of a good novel— but it’s one of the most wise and reflective divorce albums ever recorded. Ostensibly about Miranda Lambert’s split from Blake Shelton, the record never really talks about Blake at all— instead using their fissure as a catalyst for soul-searching, self-inventory, and reflection.

One of the great writerly flourishes on the album is how Lambert uses the road as a controlling metaphor— the album is structured like a rambling road trip, and imagery of vagabonds, wanderers, and prodigals pops up again and again. The very first song finds Lambert on the run, toward what she isn’t quite sure— perhaps a love that’s stronger than all of her regrets? Regardless, she is a keen chronicler of loneliness, every bit the equal of Jason Isbell, Zach Bryan, or Evan Felker.

She made this album with her studio band, and over the double-album stretch they relax into some lived-in grooves— covering everything from pedal-drenched honky-tonk weepers to rugged country-rock. Noone is better than Lambert at combining country traditionalism with contemporary punch and polish.

She is also one of our great singers, never better than she is here. On a few songs, she belts for the rafters, but for the most part she stokes the quiet embers of her voice— conjuring an alluring intimacy for a true masterpiece of interiority.

7) Peter Gabriel - So

Peter Gabriel’s 1986 classic is now fivefold platinum— making it surely one of the weirdest albums to become a big-tent pop blockbuster. Yes, it has “Sledgehammer,” Gabriel’s deliriously randy Motown tribute, and yes it has “Red Rain,” a staple of album rock radio. But from there it veers quickly into art songs, African rhythms, songs based on the infamous Milgram experiment and on the tragic life of poet Anne Sexton— this is blockbuster pop as imagined by an auteur and iconoclast, not by committee.

I have always preferred to hear the album as a series of dreams, with opener “Red Rain” setting the tone for vulnerability: “I come to you defenses down/ with the trust of a child.” Then there are repressed lusts (“Sledgehammer”) and simmering anxieties (“Don’t Give Up”) as the album winds its way into more esoteric territory— by the time “This is the Picture” comes around, Gabriel is into pure, inarticulable dream logic. With “In Your Eyes,” all his dreams and longings spill out in the language of prayer— no wonder it’s one of his most resonant songs.

So is an album of strange dichotomies. Never before and never since did Gabriel allow his arthouse experimentations and his mainstream pop instincts to coexist in such perfect parity. But it’s also an album that revels in cutting-edge synthesizer technology while also prizing indigenous rhythms, a powerful combination of innovation and traditionalism.

Its greatest balancing act is between carnality and spirituality— So is an album for body, mind, and spirit. “Sledgehammer” is brazen, but the chilling, almost-ambient “Mercy Street” is haunting in its quiet. These are the album’s two poles— the former seeking pleasure in the arms of a lover, the latter seeking solace in the arms of the Father.

8) Erykah Badu - Mama’s Gun

Mama’s Gun is an album that conveys strength and vulnerability in equal measure— Erykah Badu swings between tough-talking braggadocio and wounded self-inventory, sometimes within the course of the same song. Perhaps this is just another way of saying that Badu sounds like a real person here, endlessly relatable in how quickly she can pivot from feeling empowered to feeling like a fraud.

These big swings are rooted in heartache. It’s public knowledge that Mama’s Gun is based on Badu’s split from the rapper Andre 3000, yet somehow the album is frequently excluded from the conversation about all-time great breakup albums, a list to which it certainly belongs. Perhaps it’s because romantic dissolution is the subtext and not the text, an emotional backdrop for Badu’s self-reflection— it’s not until the epic closer “Green Eyes” that the album’s backstory is brought to the fore, casting new light on everything that came before it.

Made with the Soulquarians collective— the same squad of Black luminaries who made D’Angelo’s Voodoo and The Roots’ Things Fall Apart, among other classics— Badu’s masterwork splits the difference between conservatism and invention. It’s blessed with a warm, acoustic, live-band sound that draws from time-tested soul and R&B, but it’s also infused with modern hip-hop language and attitude. The first half of the album is stitched together as a medley, and few albums match it in terms of addictive pacing.

It’s also an album that exists in conversation with the ancestors— you can hear the spirits of Stevie Wonder, Prince, Minnie Riperton, and many others. Yet Badu’s interest isn’t in rehashing old ideas, but in expounding upon them— drawing from sounds and ideas passed down to her, she makes something arrestingly personal and richly idiosyncratic. It’s a crash course in taking sounds from the past and making them present-tense, and belongs on any list of the greatest R&B albums of all time.

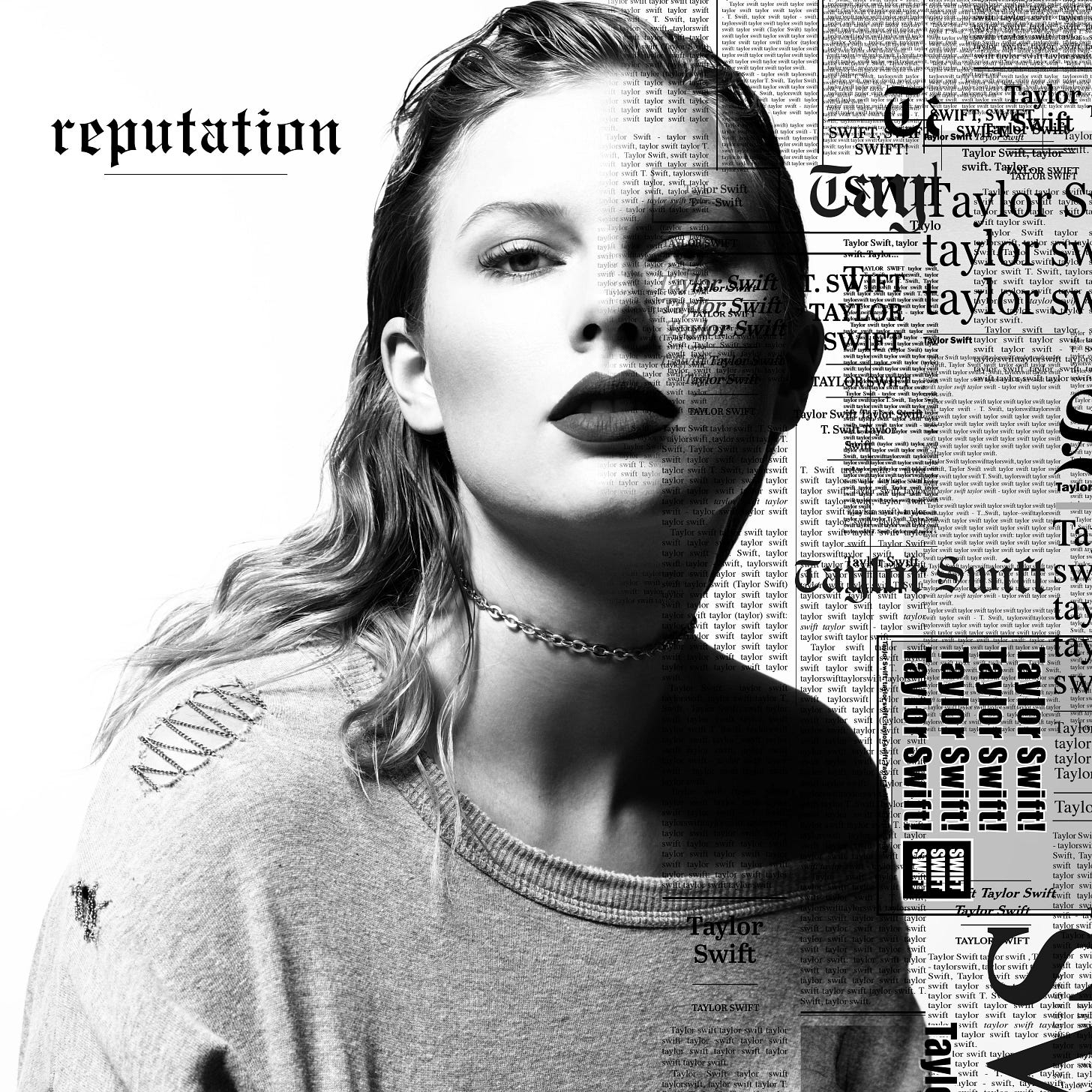

9) Taylor Swift - Reputation

It’s hard to remember now what Taylor Swift’s reputation was like in 2017, before she entered her too-big-to-fail imperial reign— but at the time, she was often derided as a boy-crazy heartbreaker who flopped from one headline-making relationship to the next. Reputation— her best and still her most misunderstood album— is one of the all-time great acts of marshalling meta-narrative in service of art. Here, she responds directly to the caricature that had been painted of her— sometimes by leaning into it like a cartoon villain, sometimes by demonstrating real soul-searching and regret, sometimes by landing body blows against her haters.

Among its many virtues, Reputation is a very funny Taylor Swift album— maybe the last time she allowed herself the freedom to be truly campy. The Right Said Fred-quoting “Look What You Made Me Do” was a confusing lead single, but in the context of the album it can be appreciated for its theatricality and panache. Much of Reputation finds Swift play-acting— blowing up different aspects of her public persona as a means to interrogate them, or to interrogate our collective response to them.

With its machine beats and glistening synthesizers, Reputation is the steeliest Swift album. And, with its more rhythmic approach, it’s the only Swift album that engages directly with hip-hop, the lingua franca of contemporary pop. Swift’s later albums often sound like they stand apart from current trends, but here she rolls up her sleeves and engages what her peers are doing— allowing it to push her and then pushing back, remaking these sounds in her own image.

Reputation is also an album drenched in desire, animated by longing. Beneath all the theatrics, beyond all the ways Swift finds to cast herself as a villain or a martyr, this is an album about intensely needing to be seen and loved. For as combative and cartoony as this record can be, it’s unmistakably a portrait of a very real person, who exhibits more vulnerability than it first seems.

10) Bettye LaVette - The Scene of the Crime

Many talented people have stories of being chewed up and spat out by the music industry— but few of those stories are as resonant as Bettye LaVette’s. The Detroit singer scored a few locally-successful singles in the 1960s and briefly toured as part of James Brown’s retinue after that— then spent decades in industry exile, her career wilting as one album after another was cancelled, underfunded, underpromoted, or shelved altogether. She tells her story on The Scene of the Crime, a hard-as-nails musical memoir released in 2017— one of the greatest soul albums of all time, and— in true LaVette spirit— one of the most overlooked.

What’s remarkable about the album is that LaVette presents her story of struggle by relying almost entirely on words penned by others— of the 10 songs included here, only one has a LaVette co-writing credit. This is a masterpiece of interpretive singing, with LaVette slipping into character on a lineup of songs written by R&B stalwarts (Ray Charles), country legends (Willie Nelson), and pop icons (Elton John) and inhabiting them as though they were written expressly for— and about— her.

From these songs she creates a mesmerizing album about age and experience, one where she refuses to play the role of the sanguine stage; instead, these songs boast of her survival instincts, settle old scores, acknowledge regrets, and scream in defiance at death itself.

She recorded the album with the Drive-by Truckers as her backing band, a pairing that might sound mismatched at first but turns out to be inspired. The Truckers are wonderfully unflashy here, providing limber grooves but staying well of LaVette’s way— models of sympathetic support. It results in a sound as hardboiled as an old black-and-white film noir— a stark tale of choices and consequences, falls from grace and unlikely shots at redemption.