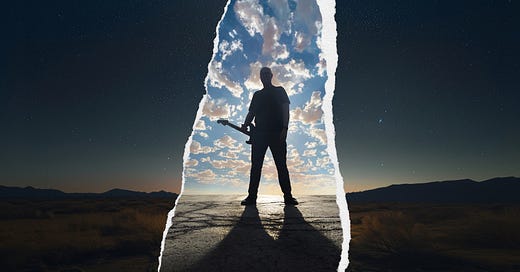

Bob Mould - Here We Go Crazy

Across the back pages of Hüsker Dü, Sugar, and a number of fine solo albums, Bob Mould has proven himself one of the true masters of the power pop idiom— an exacting craftsman whose toolset includes earworm melodies and crunching guitar riffs. In recent years, he has also become a deft chronicler of the Trump era’s anguish— not necessarily explaining or illuminating the spirit of the age, but providing a space for shared dismay and catharsis.

His latest, Here We Go Crazy, finds Mould pretty near the top of his game. I reviewed the album for FLOOD Magazine; an excerpt:

Following 2020’s bruised Blue Hearts, Here We Go Crazy is explicitly pitched as a response to the unrest of early 2025. Luckily, a grim national mood does nothing to diminish Mould’s power-pop exuberance. As a craftsman whose tools are sugar-rush melodies and loud, crunching guitar riffs, Mould is a master with very few peers; throughout the new album he confidently summons instant-earworm hooks and visceral thrills, backed by his long-serving rhythm section of drummer Jon Wurster and bassist Jason Narducy. Working with this power trio, Mould has made another rip-roaring delight, worthy of comparison to Copper Blue, the landmark 1992 album he recorded with Sugar. This muscular band is the perfect engine for Mould’s taut, terse songs. They blaze through 11 tracks in just over half an hour, the pace seldom slowing—even when Mould goes acoustic on “Lost or Stolen,” Wurster keeps things lively with a gleeful thump.

But the band really finds its sweet spot on songs like “Sharp Little Pieces,” where a scuzzy, distorted prologue quickly opens up into two minutes of propulsive melody and driving riffs. Even better are “Fur Mink Augurs,” a hardcore-adjacent maelstrom of snarl and thrash, and “When Your Heart is Broken,” featuring one of Mould’s most immediate sing-along hooks. The very title of that song suggests that the mountaintop experience that opens the album fades fast: Here We Go Crazy quickly crashes back into reality, where Mould’s lyrics gesture often toward the claustrophobic, disorienting feeling of the era. “I worry for the future, I worry for the pain / I worry myself sick about the wear and tear and strain,” he sings on standout “You Need to Shine,” and the surrounding songs maintain a similarly fretful posture.

Check out the full review, and play this album with the volume cranked all the way up.

My rating: 7.5 out of 10.

Cloakroom - Last Leg of the Human Table

In a recent Stereogum profile, writer Zach Kelly describes Indiana power trio Cloakroom as “one of the most consistently capital-H heavy” bands in the world today. The group’s sensational new album Last Leg of the Human Table certainly attests to this, but also demonstrates that there’s much more to Cloakroom than pulverizing volume and bruising physicality— that in fact their greatest gifts might be their ear for melody, their command of atmosphere, and their careful cultivation of texture.

That’s not to say there aren’t a few moments of majestic heaviness. Opener “The Pilot” could be a case study for everything connoisseurs expect from a shoegaze band— glacial pacing, cavernous bass, and beautiful melodies transmitted through richly-layered and transcendently loud guitar effects. Drummer Tim Remis brings just the right level of rambunctious energy with his jittery fills.

That rowdy spirit can scarcely be contained on the following song, “Ester Wind,” which thrashes and lurches through three minutes of scuzzy bliss— providing the kind of kinetic immediacy that would have been made it a staple of 90s alt-rock radio. Somehow the band surpasses that ragged energy on the late-album highlight “Clover Looper,” a pileup of monster riffs held together by Remis’ devastating thump.

Given Cloakroom’s reputation for capital-H heavy, some of the songs that stand out the most are the ones that seem to escape gravity. “Unbelonging” is noteworthy not just for its jangling riff— which scratches that early R.E.M. itch like nothing else has this side of Alvvays’ “After the Earthquake”— but for its floating, featherweight groove. For a band so muscular, Cloakroom impresses with their light touch.

That same light touch is evident in their curation of sonic details and compelling sound effects. “On Joy and Unbelieving” is a minute-long instrumental that begins with lo-fi strumming but evolves into a mini-tribute to Pet Sounds, twinkling bells adorned over a gentle synth pulse. Meanwhile, the twanging country-western number “Bad Larry” demonstrates the band’s ability to create wide-open spaces, their guitars echoing across desert vistas.

That same song also evinces the group’s approach to writing lyrics— philosophical, playful, and mysterious, less notable for narrative clarity than for little nuggets of earned wisdom. “I don’t know what they’re telling you/ Little things ain’t easy to lose,” goes a koan from “Bad Larry,” a perfectly chewy couplet that’s only bested by the hangdog opener to “Ester Wind”: “If you live long enough/ You’ll be laughing in disgust.”

The album ends with “Turbine Song,” another mammoth track that captures Cloakroom’s go-to trifecta of sad, slow, and loud. It’s the sound of the band happily in their wheelhouse, capping an album where they prove again and again just how versatile they can be.

My rating: 8 out of 10.

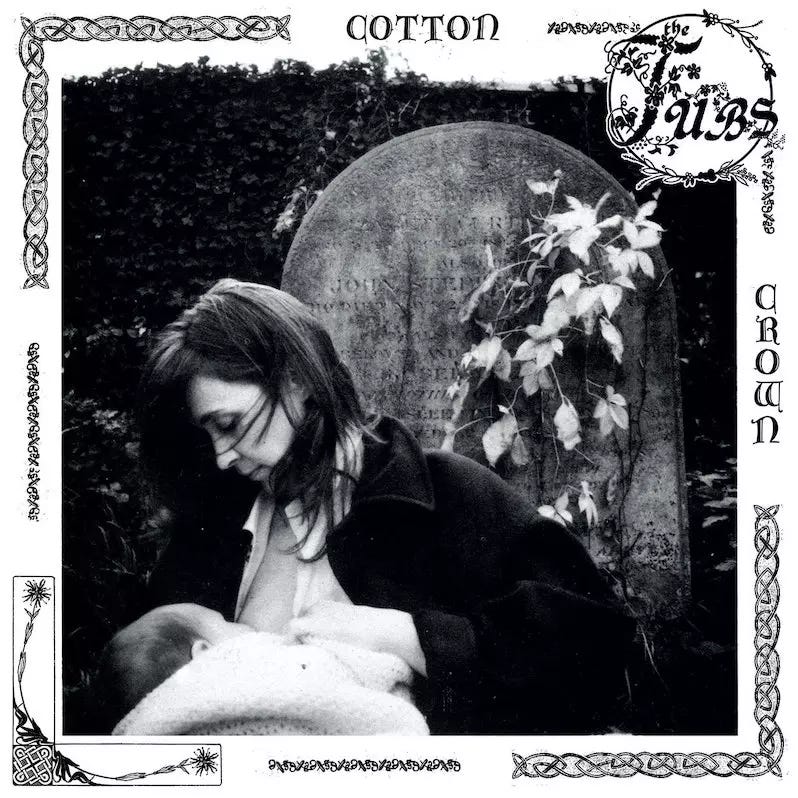

The Tubs - Cotton Crown

With what’s sure to be one of the most evocative album covers of 2025, The Tubs’ Cotton Crown lays bare its dominating thematic concerns and central narrative.

It’s a picture of a woman breastfeeding her newborn child, a gravestone looming ominously behind her. The baby is Owen “O” Williams, lead singer and principal songwriter for London’s The Tubs, and the woman is Charlotte Greig— folksinger, and Williams’ late mother. A decade ago, Greig died by suicide; Williams spent years trying to make sense of things by way of a novel, which eventually morphed into the nine-songs-in-half-an-hour that make up Cotton Crown. (The album title comes from one of Greig’s own songs; the cover image was originally used for one of her 7” singles.)

Williams’ grief became a catalyst for frenzied, cathartic creativity— he wrote the bulk of this material in a week’s time, and the songs slip between memoir and fiction, self-deprecating caricature and earnest heartache. Like grief itself, Cotton Crown avoids linearity for a jumble of acute, often-contradictory feelings. It all ends with “Strange,” which Williams has singled-out as the most autobiographical thing here, chilling in its specificity— in the first verse, Williams name-drops the local news site where he first learned of his mother’s passing.

Improbably, Cotton Crown shakes and shudders with exuberant energy— part party, part exorcism, part wake. The Tubs capture the glorious jangle of I.R.S.-era R.E.M., the tuneful fretwork of The Smiths in their prime— only here, the springy joy of jangle-pop is tainted by gothic menace, brooding melancholy. Even Williams’ voice, burred like Richard Thompson’s, feels at once hale and tart.

For evidence of the album’s emotional extremity, listen to the one-two punch of “One More Day” and “Fair Enough,” which both appear toward the end of the lineup. The former is a literal howl of pain and loss, not-quite-sweetened by the Mike Millsian harmony vocals: “One more day/ You could give me one more day.” That lyric feels ripped from a bereavement journal— though Williams delivers it more like primal scream therapy.

The latter song takes all that rage and turns it inward, shifting from a mother-child relationship to a romantic one. It maps out a nadir of self-loathing: “And when it all just falls apart/ You can blame it on my putrid heart.” In the way it interrogates self-destructive madness, it could be an admission of Williams’ own brittle state— or a gesture of empathy toward his mom.

Cotton King replicates the melodic pleasures of 80s college rock with a studious attention to detail— yet the disheveled emotions that roil these songs prevent the album from feeling musty or merely intellectual. It’s old-fashioned in its taste but vividly present in its humanity— even when it turns toward meta-commentary.

To that end, “Strange” ends the album with a deceptively cheerful bounce, and with Williams relating the story of someone he met at his mom’s funeral. “You could write a song to honor your mum,” the stranger says. “Well, whoever the hell you are/ I’m sorry, I guess this is it,” Williams responds. Here and elsewhere, he sings about grief like a man who’s been cursed— but he offers it to the rest of us like a gift.

My rating: 8 out of 10.

Other recent favorites:

I love all three of these. The Tubs album threw me off at first because, unlike their debut, it comes out of the gate sounding like Hootie/Blues Traveler/Gin Blossoms radio hits from the early 90s ... except glummer and more British. This comes across as a dig, but it's a vibe that works really well for them!